- Home

- Carolyn Wells

Patty's Fortune Page 19

Patty's Fortune Read online

Page 19

CHAPTER XIX

A DISTURBING LETTER

Then the days came when Patty could see anybody and everybody whocalled upon her. When she could be downstairs in the library or the bigcheery living-room, and, as she expressed it, be “folks” once more.

Still flowers were sent to her, still candies and fruit and daintydelicacies arrived in boxes and baskets, and friends sent books,pictures, and letters. Her mail was voluminous, so much so that NurseAdams who still tarried, was pressed into service as amanuensis andgeneral secretary.

The men had begun to be allowed to call, and Patty saw Cameron andChanning, who happened to call first.

“My, but it’s good to gaze on your haughty beauty again!” said Chick;“I’ve missed you more than tongue can tell!”

“Me too,” said Kit. “I wanted to telephone, but they wouldn’t let me.Said I was too near and dear to be heard without being seen,—like thechildren, or whoever it is.”

“I wish you had,” and Patty laughed. “I was longing to babble over atelephone, as we used to do, Kit.”

“Yes, in the early days of our courtship, when we were twenty-one!”

“Speak for yourself, John! I’ll leave it to Chick,—_do_ I looktwenty-one!”

“I should say not! You look sweet sixteen, or thereabouts.”

He was right, for Patty did look adorably young and sweet. She had on aFrenchy tea-gown of pale green silk, bubbling over with tulle frills ofthe same shade, touched here and there with tiny rosebuds. A fetchingcap of matching materials, was, Nan declared, a mere piece ofaffectation, but it accented her invalidism, and was vastly becoming.Her face, still pale from her illness, was of a waxen hue, but a warmpink had begun to glow in her cheeks and her blue eyes were as twinklingand roguish as ever.

“And what’s more,” Patty went on, “I won’t be twenty-one till nextMay,—and that’s ages away yet.”

“Yes, about half a year!” retorted Kit, “so I’m not so very far out, mylittle old lady! Did you get all the tokens I sent you?”

“Guess I did. I’m acknowledging ’em up as fast as I can. I had suchoodles of stuff. I begrudge the flowers that came while I was too lostto the world to see them, but enough have come since to make up. You’llget your receipts in due time.”

“Thanks. I was afraid mine were lost in the shuffle. I say, Patty, whencan you go out for a spin?”

“Not this week. Next, maybe.”

“Go with me first?”

“No, me,” put in Chick. “I’ve a limousine, he has only a runabout.”

“Lots more fun in a runabout. Besides, I asked you first.”

“What fun!” cried Patty, clapping her hands. “It’s like a dance. I’mgoing to have a programme. Wait, here’s one.”

Patty found an old dance programme in the desk near her, and Kit kindlyessayed to rub off the names. Then with his fountain pen he wrote overthe dances, “Limousine Ride.” “Runabout Spin.” “Walk.” “Skate.” “Opera.”“Dance.” “Matinée,” and a host of other pleasures to which Patty mightreasonably expect to be invited soon.

But she would only allow them one each, and after they had written theirnames after the motor-car rides, they were shooed away by ever watchfulNan, who would not allow Patty to become overtired.

Then, one morning, in the mail came a communication from Mrs. VanReypen’s lawyer. It informed Patty of the legacy left her. As Mrs. VanReypen had said, there was a bequest of fifty thousand dollars to Pattyherself, and another fifty thousand in trust for a fund for a Children’sHome. The details of the institution were left entirely to Patty’sdiscretion, and she was instructed, if in need of more funds, to applyto Philip Van Reypen.

Also was enclosed a note which Mrs. Van Reypen had written and directedto be given to Patty after her death.

“I’m afraid to open it, Nan,” said Patty, trembling as she looked at thesealed epistle.

“I don’t wonder you feel so, dear. Let me read it first.”

Gladly Patty passed it over, for she had no secrets from Nan, and hernerves were not yet as strong as before her illness.

Nan read it, and then said. “You need have no fear, Patty, it’s a dearnote. Listen:

“My Dear Little Patty:

“I am afraid I made you sorrowful when I talked to you and urged you to promise the thing I asked of you. But don’t feel hard toward me. I have your interests at heart as well as Philip’s, and I know that what you have promised will mean your life’s happiness. Now, about the Children’s Home. If you feel that after all it is too great a tax on your time or strength to take it in charge, don’t do so. Turn it all over to some one else. You and Philip can decide on the right person for the work. But I trust you will have an interest in it, and see to it that the furnishings and little comforts are as you and I would choose were we working together. This note, dear, is to say good-bye. I shall not see you again, but I die content, knowing you will love and look after my boy. It seemed strange at first to your girl heart, but you will come to love him as your own, and your life together will be filled with joy and peace. Good-bye, my child, have a kindly remembrance in your heart for your old friend,

“LADY VAN.”

Patty was crying as Nan finished. It so brought back the fine buteccentric old lady, and so renewed that dreadful promise, that the girlwas completely upset.

“You see,” she sobbed, “I’ve got to marry him. This is like a voice fromthe grave, holding me to my vow. Isn’t it, Nan?”

“Patty, look here. Do you want to marry Phil, or don’t you?”

At the quick, sharp question, Patty looked up with a start.

“Honest, Nan, I don’t know.”

“Then you ought to find out. It’s this way, Patty. If you do want tomarry him, or if you are willing to, there’s no use in fussing over thispromise business. If you don’t, and if you are sure you don’t, then youmust break that promise. But, you’ve got to be sure first.”

“How can I be sure?”

“Is there anybody else you care for?”

“N—no.”

“Kit Cameron is very much in love with you, Patty. He asked me when youwere ill, if I thought he had a chance. Has he?”

“Not the ghost of a chance! Kit’s an old dear, and I like him a heap,but he’s a worse flirt than I am. Mercy, Nan, I wouldn’t marry him for aminute!”

“Chick Channing?”

“No. He’s a lovely boy to play around with, but not to take for a lifepartner. Oh, well, I s’pose it’ll have to be Phil, after all.”

“Your father and I would like that.”

“And Mrs. Van Reypen seemed to think she’d like it; and I feel quitesure Phil would like it; and it doesn’t matter about little old me!”

“Patty! stop talking like that! You know nobody wants you to do a thingyou don’t want to do! And don’t get mad at your Nan, who has only yourbest interests at heart!”

“’Deed I won’t! I’m a brute! A big, ugly, horrid brute! Nansome, you’remy good angel. Now, let’s drop this subject for a time,—or I’ll get sonervous I’ll fly to the moon!”

“Of course you will! And you’re not going to be bothered out of yourlife, either. You put it all out of your mind, and come with me, out fora ridy-by. Then back and have a nice little nap. Then a ’normous bigluncheon; and then dress yourself all up pretty for callers.”

“What an entrancing programme! Nan, sometimes I think you’re a genius! Isure do!”

The enticing programme was carried out, and that afternoon Van Reypencame to call. It was the first time he had seen Patty since her illness,and she rather dreaded the meeting.

But Philip was so cheery and kindly that Patty felt at ease at once.

“Dear little girl,” he said, taking both her hands, “how good to see youlooking so well. I’ve been _so_ anxious about you.”

&n

bsp; “Needn’t be any more,” said Patty, smiling up at him. “I’m all well now,and never going to be sick again. But I’ve been feeling very sorry foryou, Phil.”

“Thank you, dear. It is hard, the old house seems so empty and lonely.But Aunty Van rather wanted to go, and she bade me think of her onlywith pleasant memories, and not with mourning.”

“She was always thoughtful of others’ feelings. And, Phil, how she didlove you.”

“She did. And you, too; why, I never supposed she could care for any oneoutside our family as she cared for you.”

“She was awfully kind to me.”

“And you were to her. You were mighty good, Patty, to put up with herqueer little notions the way you always did. And I say, do you know whatshe told me just before she died? She told me that you said you wouldlearn to love me. Oh, Patty, did you? I don’t doubt her word, butsometimes she thought a thing was so, when really it was only her strongwish. So I _must_ ask you. I didn’t mean to ask you today,—I meant towait till you are strong and well again. But, darling, you look so sweetand dear, and I haven’t seen you for so long, I can’t wait. Tell me,Patty, _did_ you tell Aunty Van that?”

Patty hesitated. A yes or no here meant so much,—and yet she couldn’tput him off.

“Tell me,” he urged; “you must have said something of the sort. Even ifshe exaggerated, she wouldn’t make it _all_ up. What did you tell her,dear?”

The two were alone in the library. The dusk was just beginning,—thelights not yet turned on. Patty, in a great easy chair, sat near thewood fire, which had burned down to a few glowing embers. Van Reypen,restless, had been stalking about the room. Now, he came near to her,and pushing up an ottoman, he sat down by her.

“You must tell me,” he said, in a low, tense voice. “I can’t bear it ifyou don’t. I won’t ask you anything more,—I’ll go right away, if yousay so,—but, Patty, dearest, tell me if you told Aunty Van that youwould learn to love me.”

Phil’s dark, handsome face looked into her own. With a feeling as of atightening round her heart, Patty realised that his eyes were very likehis aunt’s, that their impelling gaze would yet make her say yes. And,fascinated, she gazed back, until, coerced, she breathed a low “yes.”

Then, appalled at the look that came to his face she covered her eyeswith her hands, whispering, “Go away, Phil. You said you’d go away if Iwanted you to, and I do want you to. Please go.”

Van Reypen leaned nearer. “I will go, Little Sweetheart. I can bear togo now. You have made me so happy with that one little word. The restcan wait. Good-bye, you will call me back soon, I know.”

Bending down he dropped a light kiss on the curly golden hair, and wentaway, happy in the knowledge of Patty’s love, and almost amused at whathe thought was her shyness in acknowledging it.

When she heard the street door close, Patty looked up. Her face waswhite, and she was nervously trembling.

“Tell me if you told Aunty Van that you would learn tolove me”]

“Nan,” she called; “Nan!”

Nan came in from another room. “What is it, Patty, dear? Where isPhilip?”

“He’s gone. Oh, Nan, I kept my promise.”

“You did! What do you mean? Are you engaged to Philip? Then why did hego?”

Patty laughed, but it was a little hysterical. “I sent him away. No,we’re not engaged, that is, I don’t think we are. But I suppose we willbe.”

“Patty, behave yourself. Brace up, now, and tell me what you’re talkingabout. Any one would think getting engaged was a funeral or some suchoccasion!”

Patty shook herself, and smiled at Nan.

“I am a goose, I suppose. I don’t know whether I’m glad or sorry, but Itold Phil I’d learn to love him.”

“H’m, I don’t see as you’ve bound yourself to anything very desperate!You can doubtless learn, if you study hard enough.”

“Don’t tease me, Nan. I’m not sure I want to learn.”

“Then don’t! Patty, sometimes you’re perfectly ridiculous!”

“Huh! Just ’cause _you_ happened to get a perfectly splendid man like myfather, and didn’t have to think twice, you think _everybody_ can decidein a hurry!”

Nan burst into laughter. “Oh, you are _too_ funny!” she cried, and Pattyhad to laugh, too.

“I suppose I am,” she said, dolefully, “to you. But to me it doesn’tseem funny a bit.”

“Forgive me, dear,” said Nan, repentantly; “I won’t laugh any more. Tellme about it.”

“It’s that old promise thing. Mrs. Van told Phil I had told her I wouldlearn to love him, and he asked me if I did. And I had to say yes. Andof course I couldn’t tell him she _made_ me promise. Now, could I?”

“I don’t know. It _is_ a little serious, Patty, unless, as I saidbefore, unless you want to learn to love him. Do you?”

“I don’t know, but I don’t think so. I wish to goodness he wouldn’tbother me about it!”

“He sha’n’t! Patty, it is a shame for you to be bothered if you don’twant to be. Now, I’ll help you out. I’ll tell Phil, myself, that you’renot well enough yet to be troubled about serious matters, and he mustwait till you are. He won’t be angry, I can explain it to him.”

“I don’t care whether he’s angry or not. It isn’t that, Nan. It’s thatjust the little bit I said to him, he takes to mean—everything.”

“Of course he does, Patty. You can’t tell a man you’ll learn to love himunless you mean that you expect to succeed and that you’ll marry him.What else _could_ you mean?”

“Of course, if I said it of my own accord. But, don’t you see, Nan, thatI only said it because I promised her I would, and it doesn’t seem fair,that I should have to say it because she made me.”

“You’re right, Patty, it _doesn’t_. And you ought not to be held by thatinfamous performance! I just begin to see it as it is, and I am notgoing to have you tortured. You don’t really love Phil, or you’d knowit; and this ‘promise’ and ‘learning to love him’ is all foolishness.I’m going to tell him, or have Fred do so, of that promise business, andthen if he wants to ask you again, and let you answer of your own will,and not by anybody’s coercion, very well.”

“Oh, Nan, what a duck you are! What would I ever do without you! Willyou really do that? I tried to tell Phil how it was, but he wasso—so——”

“Precipitate?”

“Yes, that; but I meant more that he was so glad to have me say that_yes_, that it seemed too bad to tell him that awful story about hisaunt.”

“It _is_ an awful story, but he ought to know it. Why, he’d rather knowit. You two couldn’t live all your lives with that secret betweenyou—could you?”

“Of course we couldn’t.”

“And then, too, it isn’t fair to him. If you’re answering his questionunder duress,—I never did know what duress meant,—but anyway, ifyou’re answering his questions at his aunt’s commands, he certainlyought to know it. It’s wrong to let him think it’s your own answer, ifit isn’t.”

“That’s so,” and Patty looked greatly relieved. “Say, Nan, when can youtell him?”

“Oh, I can’t do it. I’ll get your father to. He’s the proper one,anyway.”

“Yes, I guess he is,” sighed Patty. “Oh, what do poor little girls dowho haven’t such kind parents? And now I wonder if it isn’t time for mybeef tea!”

CHAPTER XX

BETTER THAN ANYBODY ELSE

It was the next afternoon that Farnsworth called. He had not seenPatty since the day she was so very ill, but he had telephoned or calledevery day to inquire after her. Today he was allowed to see her, and ashe entered the library, his face was radiant with sunny smiles.

Patty looked up, smiling too, and held out her hands in greeting. Fromthe lace cap that crowned her hair, to the tips of her dainty slippers,she was all in white, and her pale face and waxen hands made her look solike an angel that big, strapping Bill held his breath

as he looked ather.

“Are you really there?” he asked; “are you fastened to earth? I somehowfeel afraid you’ll waft off into the ether, you look so ethereal.”

“No, indeed! I’m here to stay. I’ve a pretty strong liking for this oldworld and I’ve no desire to flee away just yet.”

“Good! It’s great to see you again,” and Farnsworth took a seat besideher. “I’m thinking you’ll be getting out of doors soon.”

“I hope so. But I’m having a beautiful time convalescing. Everybody isso good to me, and I’m showered with presents, as if I were—engaged!”

“And I hear that you are.” Bill looked at her steadily. “I’m told thatyou’re betrothed to Van Reypen, and I want to be among the first to wishyou all the joy there is in the world.”

“Who told you?” and Patty looked startled.

“A little bird,” Farnsworth smiled at her gently. “I am very glad foryou, dear. Philip is a big, strong-hearted chap, and he can give you allyou want and deserve.”

“’Most anybody could do that,” said Patty, a little shortly, for itseemed to her that Farnsworth took the news of her engagement rathereasily.

“No. I couldn’t. There are not many men like Van Reypen; rich,well-born, intellectual, and kind. Moreover, he has prestige and anacknowledged place in the best society; all of which goes to make up theatmosphere of life that best suits you,—you petted butterfly.”

Bill’s smile robbed the words of any effect of satire or reproof.

“Am I a feather-headed rattlepate?” and Patty treated the young man toher best and prettiest pout.

“Not entirely. But you like to have all about you in harmony and goodtaste. Nor are you to blame. You are born to the purple,—and all thatthat signifies.”

“Aren’t you?”

“I?” Farnsworth looked amazed. “No, Patty; I am what they call aself-made man. My people are plain people, and my childhood was one ofrough experiences,—even hardships.”

“All the more credit to you, Little Billee, for turning out a polishedgentleman.”

“But I’m not, dear. I’ve picked up enough of social customs not to makeawkward mistakes, but I have not the innate breeding of the VanReypens.”

Farnsworth was not looking at Patty, he was staring into vacancy, andlooked as if he were talking more to himself than to her.

“Rubbish!” said Patty, gaily, annoyed at herself for feeling the truthof his words. “You’re a splendid old Bill, and whoever says a wordagainst you is no friend of mine! So be careful, sir, what you sayagainst yourself.”

“You’re a loyal little friend, Patty, and I’m more glad than you canrealise to know that it is so. Now, you’re going to do all you can togrow stronger, aren’t you? It hurts me to see you so white andwan-looking. I wish I could give you some of my big strength,—I’ve morethan I know what to do with.”

At this speech Patty blushed a rosy crimson, and Farnsworth’s remarkabout her wan looks lost its point.

“Why the apple blossoms in your cheeks, Little Girl?” and he smiled ather evident confusion.

“Would you give me of your strength, Bill,—if—if Iwere—were—dying——”

“Wouldn’t I! I’d snatch you back from old Charon, if you had one foot inhis boat!”

Patty looked at him, with a queer uncertainty in her eyes. Twice shetried to say something, and couldn’t; and then Farnsworth said softly:

“As I did,—although I doubt if you knew it.”

“Did you, Billee? _Really?_ I thought it was a dream,—wasn’t it?”

“You mean—that day——”

“Yes.”

“No, Patty, it was not a dream. I chanced to come in, and when I askedabout you, you must have heard my voice, for you called out to me——”

“And you came.”

“Yes. And you wanted some of my strength,—I gave it to you by puttingyou to sleep. That was what you needed most.”

“Was that the crisis, Bill?”

“They said so, dear. I am glad I could help.”

“You saved my life.”

“I’m not sure of that, but I wish I had, for you know there is aconvention that gives saved lives to the savers.”

“Take it, then,” said Patty, impulsively.

Farnsworth gave her a long look. “I wouldn’t want it because you thoughtyou _ought_ to give it to me.”

“Yet that is why I’m giving it to Philip.”

“He didn’t save your life!”

“No, I mean I’m giving it to him because I think I ought to.”

“What _do_ you mean?”

And then Patty told him the whole story of her promise to Mrs. VanReypen, and her consequent enforced betrothal to Philip.

Farnsworth’s blue eyes opened wide. “And he takes you on those terms!”

“Oh, he doesn’t know about the promise. But what else can I do, LittleBillee? I can’t break a promise made to a dying woman, and—too—I likePhil——”

“Like isn’t enough,” said Farnsworth, sternly. “Do you love him, Patty?”

“I—I guess so——” she stammered, a little frightened at his vehemence.

And at that very moment Philip Van Reypen appeared.

“Hello, Peaches,” he said gaily to Patty. “How do, Farnsworth? And how’sour interesting invalid today?”

“I’m fine,” returned Patty. “Getting better by the minute. ’Spect to goout coasting soon. Better get your sleds ready, we may have snow anyday——”

Patty was babbling on to cover a certain constraint in the attitude ofthe two men. But almost immediately, Farnsworth took his leave, gentlydeclining Patty’s plea to stay longer.

“Let him go,” said Philip, as the street door closed behind Bill; “Iwant to see you alone. See here, Patty, what’s this about a promise toAunty Van?”

“Who told you?”

“Your father. Sent and asked me to come to his office, so I went, and hetold me the whole story. You poor little girl! I’m _so_ sorry ithappened, and I’ve come to ask you to forgive Aunty Van. She was allwrong to do such a thing, but honestly, she was actuated by rightmotives. She loved you so, and she loved me, and she was so sure we weremade for each other. I’m sure of that, too,—but if you’re not, you’reto say so, and not think you’re bound by a promise to _anybody_.”

“But I did promise her——”

“Forget it! In your dealings with me, you’re to deal only with me.There’s no go-between or dictator or even adviser; only just our twoselves. But before we begin on our affairs, I want this other mattersettled for all time. Promise me that you will never again even think ofthat promise that she wrung from you. You _must_, or I can’t have lovingmemories of Aunty Van. Also, I want you to tell me truly, whether youwant to look after the Children’s Home scheme or not. If it’s a burden,you’re not to have anything to do with it. See?”

“How kind you are, Phil. Yes, I do want to help with the Home project,but I don’t want to be at the head of the Board,—or whatever has chargeof it. I want to tend to the furnishings and little comforty things forthe kiddies, but can’t somebody else build it?”

“Of course they can! You dear Baby, do you think you’re to have all thaton your poor little shoulders? It shall all be just as you say. And youare to do as much or as little as you like. Of course, you’re not evento think of it, till you’re all well and strong again. Now, as to yourown bequest from Aunty Van. I can’t tell you how glad I am she left youa little pin-money——”

“A little pin-money!” exclaimed Patty, raising her eyes heavenward.

“Well, an enormous fortune,—if you like that better. But at any rate,it’s yours, to do as you please with. I don’t suppose you really needit, but——”

“I don’t need it for myself, Phil, but oh, I’m going to do such lovelythings with it for my girls! I shall use it for their vacation tripsand—that is, part of it. Part of it, I’m going to spend on myself—oh,I have the delightfullest plans!”

> “All right, Pattykins, do what you will, as long as it pleases your owndear self. And now, we come to what interests me most. I decline to haveyou for my very own, if you consent _only_ because Aunty Van made youpromise to do so. Cut that all out,—and let’s begin again. Will youpromise me,—_me_, mind you,—not any one else _for_ me,—to learn tolove me?”

And now Patty was her own roguish self again. The release from thebugbear promise was so great, that she considered gaily what Phil wasasking now.

“Well,” she began, looking provokingly pretty, “suppose I say I’ll _try_to learn to love you——”

“Oh, try—to endeavour—to attempt—to make a stab at it! But, allright, I’ll take that crumb of a promise. You’ll _try_ to learn to loveme. Patty, _I’m_ going to be the teacher, and if you’ll try,—and you’llhave to, since you’ve promised,—by Jove, I’ll _make_ you learn!”

“Very well,” and Patty’s eyes danced; “when you going to begin?”

“Right off, this minute. And never stop, short of success?”

Van Reypen looked very handsome, his dark hair tossed back from hisbroad forehead, his dark eyes alight with love and determination. He wasthe sort of man who meets any circumstances with gracefulun-selfconscious ease, and he sat back in his chair, looking at Pattywith an air of assured proprietorship, that amused rather than irritatedher.

“But I’m not engaged to you,” and Patty shook her lace-capped head tillher curls bobbed.

“No? Oh, _do_ be! Let’s be _that_, at least.”

“What! engaged before I’ve learned to love you! Nevaire!”

“All right, Sweetness. I’ll wait. But it won’t be long. The poet babblesof ‘love’s protracted growing,’ but ours won’t be so terriblyprotracted, I promise you! I’ll give you a week to decide in,—andthat’s too long——”

“A week! I couldn’t begin to get ready to think about it in that time!Give me a month, and I’ll go you.”

“All right, your wish is law. A month from today, then, you’re tocomplete your lessons, and graduate a full-fledged ladylove of yourhumble servant.”

“I don’t think you’re so awfully humble, Philip.”

“Can’t be, while I have you to be proud of! Oh, Patty, do decidequicker’n a month! That seems a century! Say a fortnight.”

“Nope. A month it is, before I need to say yes or no to your question.One more month of gay girlish freedom. Oh, Phil, I couldn’t be tied downto any one man! I want to flirt with all of them!”

“Do it in this month, then. For I warn you, after thirty-one more days,your flirtations must be laid aside, with your wax doll and Britanniateaset.”

“You seem pretty positive!”

“Faint heart never won fair lady. I’ve lots of faults, but a faint heartisn’t one of them. You’re the girl for me, but you don’t quite know itfor sure,—_yet_. So I’m going to show you the truth, and gently butfirmly lead you to it!”

Philip kept the conversation in this light key, and when he went away,Patty retained the impression of a very charming afternoon with him.

“He _is_ nice,” she said to Nan, after telling her all about it; “Youfeel so sort of sure of him all the time. He always does the rightthing.”

“Yes,” said Nan.

Next day brought many visitors, but among the most welcome was BabyMilly, or Middy, as she called herself, and as Patty always called her.

“Such a booful Patty!” the child exclaimed, delighted at seeing heragain after so long a time. “Middy loves you drefful! See, Middy b’ingedlot o’ Naws!”

“She means Noahs, ma’am,” explained the nurse who had Milly in charge.“They’re the dolls from her Noah’s Ark.”

Sure enough, the baby had the four straight-garmented puppets thatrepresent in painted wood, the patriarch and his three sons.

They were up in Patty’s boudoir and the little one gaily stood hercherished toys round among the small ferns in the window-box.

Suddenly Patty grabbed her up and carried her off to have a feast ofbread and jam and milk.

“Nice party,” the guest remarked. “Des Patty an’ Middy. Ve’y niceparty.”

After the party, the little one was taken home, and so it was not untilshe went to her room that night, that Patty discovered the four “Naws”still marching through her ferns.

“Blessed baby!” she said to herself, as she collected the illustriousquartette, and laid them on the table to be returned to their owner thenext day.

Then Patty threw herself in a big chair, to think over her problems. Shehadn’t told Farnsworth that she was not now engaged to Philip, and shedidn’t quite like to tell him, though why, she couldn’t say.

“I wonder who I like best of anybody in all the world,” she mused, asshe played idly with Middy’s toys. “I’m as uncertain of that, as I amwhich of these four statuettes I prefer.”

She looked critically at the Noah, and at Shem, Ham and Japheth; alittle undecided as to which was which, so similar were they in everyrespect save as to the colours of their long one-piece gowns.

She stood them in a row on the table. “That’s Philip,” looking at one ofthem; “that’s Little Billee; that’s Kit, and the yellow one is ChickChanning. I’ve come to like Chick a lot,—more’n Kit, I believe. Now,let’s see. S’pose I had to lose one of these four forever; which could Ibest spare.”

The game grew exciting. Patty, sitting on one foot, leaned toward thetable, middle finger-tip caught against her thumb, ready to snap theleast desirable into limbo.

“Sorry,” she said, “but old Kit must go.” She snapped her fingers, andluckless Kit flew across the room.

Patty’s face fell. “It’s a hard world! But I’m going to fight this thingto a finish. And there’s no use mincing matters, if another had togo—it would, of course, be Chick.”

Another flick of her slender fingers, and Channing flew up in the airand landed on the high mantel.

“Now then,” and Patty knew that a momentous decision lay before her.There remained Philip and Bill Farnsworth.

Patty clasped her hands, rested her chin upon them and stared at thebrown and red-coated gentlemen still standing before her.

“Phil is such a dear,” she reasoned, as if trying to convince herself;“and he certainly does worship the ground I walk on. But there’ssomething about Bill—dear Little Billee! I wonder what it is abouthim—And he _did_ save my life—I think I like him for his strength. Inever saw anybody so strong—he always makes me think of SirGalahad;—‘His strength was as the strength of ten because his heart waspure.’ Little Billee’s heart is pure,—pure gold. I—somehow, I know itby a sort of intuition. And yet, Phil—oh, Philip is a gentleman, ofcourse, I know that, but Bill is nature’s nobleman—well any way, justat this minute, I like Little Billee better than anybody in the world!So, there now!”

With a well-aimed flick of her fingertips, Patty set Philip spinning,and it was a week later that she found him in her work-basket.

She had the grace to look a little ashamed of herself, but the fire ofdetermination was in her eye, and a rosy flush tinted her cheeks.

Then a mischievous smile came to the corners of her mouth, and on animpulse she caught up the telephone from the stand, and called theExcelsior Hotel.

In a few moments Farnsworth’s “Hello” sounded in her ear.

“It’s Patty,” she said, in a small, timid voice.

“Well, I’m glad. Are we to have a little chat?”

“No,—I just wanted to tell you—to tell you——”

“Yes; dear Little Girl,—what is it?”

“I can’t seem to tell you after all.”

“Shall I come over there?”

“Oh, no, it’s too late. I only wanted to say that—that I’m not reallyengaged to anybody—now.”

“Thank heaven! and,—do you want to be?”

“Oh, no! Not for a month. I’ve got that long to make up my mind in.”

“Good! May I see you in the meantime?”

<

br /> “Not unless you take that laugh out of your voice! I do believe you’remaking fun of me.”

“I can’t help a laugh in my voice when the dull world has suddenlyturned to rosy sunlight! Tell me, Apple Blossom, is that all you calledup to say?”

“No,” and Patty’s eyes grew luminous; “I _was_ going to say somethingelse——”

“What was it,—tell me,—Patty-sweet,——”

“Only—that at this present moment,—just for _one little minute_, youknow, I like—you—better—than—anybody else in all the world!”

And with a sudden click, Patty hung up the receiver, and buried herburning face in her hands.

* * * * *

Transcriber’s note:

Hyphenation and spellings have been retained as in the original.

Punctuation and type-setting errors have been corrected without note.

Other errors have been corrected as noted below:

page 164, something in Fred Fairchild’s ==> something in Fred Fairfield’s

page 226, I have have had a ==> I have had a

The Deep Lake Mystery

The Deep Lake Mystery The Man Who Fell Through the Earth

The Man Who Fell Through the Earth The Mystery of the Sycamore

The Mystery of the Sycamore The Mystery Girl

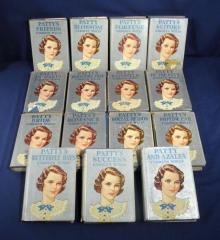

The Mystery Girl Patty Blossom

Patty Blossom Patty and Azalea

Patty and Azalea The Room with the Tassels

The Room with the Tassels The Vanishing of Betty Varian

The Vanishing of Betty Varian Murder in the Bookshop

Murder in the Bookshop The Staying Guest

The Staying Guest The Curved Blades

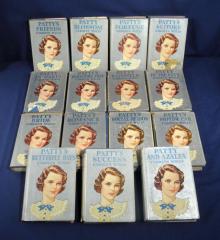

The Curved Blades Patty—Bride

Patty—Bride The Mark of Cain

The Mark of Cain Two Little Women on a Holiday

Two Little Women on a Holiday Marjorie's New Friend

Marjorie's New Friend Patty's Fortune

Patty's Fortune Patty's Social Season

Patty's Social Season Patty in Paris

Patty in Paris The Diamond Pin

The Diamond Pin The Come Back

The Come Back The Dorrance Domain

The Dorrance Domain Marjorie at Seacote

Marjorie at Seacote Patty's Butterfly Days

Patty's Butterfly Days Patty's Motor Car

Patty's Motor Car Patty's Success

Patty's Success Patty's Suitors

Patty's Suitors Patty's Summer Days

Patty's Summer Days Two Little Women

Two Little Women Patty Fairfield

Patty Fairfield Marjorie's Busy Days

Marjorie's Busy Days Betty's Happy Year

Betty's Happy Year In the Onyx Lobby

In the Onyx Lobby Marjorie's Maytime

Marjorie's Maytime The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK®

The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK® The Gold Bag

The Gold Bag The Clue

The Clue The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery

The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery