- Home

- Carolyn Wells

The Diamond Pin

The Diamond Pin Read online

THE DIAMOND PIN

* * * * *

CAROLYN WELLS'

_Baffling detective stories in which Fleming Stone, the great American Detective, displays his remarkable ingenuity for unravelling mysteries_

VICKY VAN $1.35 net THE MARK OF CAIN $1.35 net THE CURVED BLADES $1.35 net THE WHITE ALLEY $1.25 net ANYBODY BUT ANNE $1.25 net THE MAXWELL MYSTERY $1.25 net A CHAIN OF EVIDENCE $1.25 net THE CLUE $1.25 net THE GOLD BAG $1.25 net

EACH WITH FRONTISPIECE IN COLOR.12MO. CLOTH.

* * * * *

FIBSY AIMED IT STRAIGHT AT THE MASKED MAN--_Page 258_]

THE DIAMOND PIN

by

CAROLYN WELLS

Author of "A Chain of Evidence," "Vicky Van," etc.

With a Frontispiece in Color by Gayle Hoskins

Philadelphia and LondonJ. B. Lippincott Company1919

Copyright, 1919, by J. B. Lippincott Company

CONTENTS

CHAPTER PAGE I. A CERTAIN DATE 7 II. THE LOCKED ROOM 24 III. THE EVIDENCE OF THE CHECKBOOK 40 IV. TIMKEN AND HIS INQUIRIES 56 V. DOWNING'S EVIDENCE 71 VI. LUCILLE 87 VII. THE CASE AGAINST BANNARD 103 VIII. RODNEY POLLOCK APPEARS 119 IX. IRIS IN DANGER 135 X. FLOSSIE 151 XI. GONE AGAIN! 167 XII. IN CHICAGO 183 XIII. FLEMING STONE COMES 200 XIV. FIBSY AND SAM 216 XV. IN THE COLOLE 233 XVI. KIDNAPPED AGAIN 250 XVII. THE CIPHER 266 XVIII. SOLUTION AT LAST 282

CHAPTER I

A CERTAIN DATE

"Well, go to church then, and I hope to goodness you'll come back in amore spiritual frame of mind! Though how you can feel spiritual in thatflibbertigibbet dress is more than I know! An actress, indeed! Nomummers' masks have ever blotted the scutcheon of my family tree. TheClydes were decent, God-fearing people, and I don't propose, Miss, thatyou shall disgrace the name."

Ursula Pell shook her good-looking gray head and glowered at her prettyniece, who was getting into a comfortable though not elaborate motorcar.

"I know you didn't propose it, Aunt Ursula," returned the smiling girl,"I thought up the scheme myself, and I decline to let you have credit ofits origin."

"Discredit, you mean," and Mrs. Pell sniffed haughtily. "Here's somemoney for the contribution plate. Iris; see that you put it in, anddon't appropriate it yourself."

The slender, aristocratic old hand, half covered by a falling lacefrill, dropped a coin into Iris' out-held palm, and the girl perceivedit was one cent.

She looked at her aunt in amazement, for Mrs. Pell was a millionaire;then, thinking better of her impulse to voice an indignant protest, Irisgot into the car. Immediately, she saw a dollar bill on the seat besideher and she knew that was for the contribution plate, and the penny wasa joke of her aunt's.

For Ursula Pell had a queer twist in her fertile old brain that made herenjoy the temporary discomfiture of her friends, whenever she was ableto bring it about. To see anyone chagrined, nonplused, or made suddenlyto feel ridiculous, was to Mrs. Pell an occasion of sheer delight.

To do her justice, her whimsical tricks usually ended in thegratification of the victim in some way, as now, when Iris, thinking heraunt had given her a penny for the collection, found the dollar readyfor that worthy cause. But such things are irritating, and wereparticularly so to Iris Clyde, whose sense of humor was of a differenttrend.

In fact, Iris' whole nature was different from her aunt's, and thereinlay most of the difficulties of their living together. For there weredifficulties. The erratic, emphatic, dogmatic old lady could notsympathize with the high-strung, high-spirited young girl, and as aresult there was more friction than should be in any well-regulatedfamily.

And Mrs. Pell had a decided penchant for practical jokes--than whichthere is nothing more abominable. But members of Mrs. Pell's householdput up with these because if they didn't they automatically ceased to bemembers of Mrs. Pell's household.

One member had made this change. A nephew, Winston Bannard, had resentedhis aunt's gift of a trick cigar, which blew up and sent fine sawdustinto his eyes and nose, and her follow-up of a box of Perfectos wasinsufficient to keep him longer in the uncertain atmosphere of herotherwise pleasant country home.

And now, Iris Clyde had announced her intention of leaving the old roofalso. Her pretext was that she wanted to become an actress, and that wastrue, but had Mrs Pell been more companionable and easy to live with,Iris would have curbed her histrionic ambitions. Nor is it beyond thepossibilities that Iris chose the despised profession, because she knewit would enrage her aunt to think of a Clyde going into the depths ofignominy which the stage represented to Mrs. Pell.

For Iris Clyde at twenty-two had quite as strong a will and inflexible adetermination as her aunt at sixty-two, and though they oftenest ranparallel, yet when they criss-crossed, neither was ready to yield thefraction of a point for the sake of peace in the family.

And it was after one of their most heated discussions, after a duel ofwords that flicked with sarcasm and rasped with innuendo, that Iris,cool and pretty in her summer costume, started for church, leaving Mrs.Pell, irate and still nervously quivering from her own angry tirade.

Iris smiled and waved the bill at her aunt as the car started, and thensuddenly looked aghast and leaned over the side of the car as if she haddropped the dollar. But the car sped on, and Iris waved frantically,pointing to the spot where she had seemed to drop the bill, andmotioning her aunt to go out there and get it.

This Mrs. Pell promptly did, only to be rewarded by a ringing laugh fromIris and a wave of the bill in the girl's hand, as the car slid throughthe gates and out of sight.

"Silly thing!" grumbled Ursula Pell, returning to the piazza where shehad been sitting. But she smiled at the way her niece had paid her backin her own coin, if a dollar bill can be considered coin.

This, then, was the way the members of the Pell household were expectedto conduct themselves. Nor was it only the family, but the servants alsowere frequent butts for the misplaced hilarity of their mistress.

One cook left because of a tiny mouse imprisoned in her workbasket; onefirst-class gardener couldn't stand a scarecrow made in a ridiculouscaricature of himself; and one small scullery maid objected tounexpected and startling "Boos!" from dark corners.

But servants could always be replaced, and so, for that matter, couldrelatives, for Mrs. Pell had many kinsfolk, and her wealth would prove astrong magnet to most of them.

Indeed, as outsiders often exclaimed, why mind a harmless joke now andthen? Which was all very well--for the outsiders. But it is far frompleasant to live in continual expectation of salt in one's tea or cottonin one's croquettes.

So Winston had picked up his law books and sought refuge in New YorkCity and Iris, after a year's further endurance, was thinking seriouslyof following suit.

And yet, Ursula Pell was most kind, generous and indulgent.

Iris hadbeen with her for ten years, and as a child or a very young girl, shehad not minded her aunt's idiosyncrasy, had, indeed, rather enjoyed thefoolish tricks. But, of late, they had bored her, and their constantrecurrence so wore on her nerves that she wanted to go away and orderher life for herself. The stage attracted her, though not insistently.She planned to live in bachelor apartments with a girl chum who was anartist, and hoped to find congenial occupation of some kind. She ratherharped on the actress proposition because it so thoroughly annoyed heraunt, and matters between them had now come to such a pass, that theyteased each other in any and every way possible. This was entirely Mrs.Pell's fault, for if she hadn't had her peculiar trait of practicaljoking, Iris never would have dreamed of teasing her.

On the whole, they were good friends, and often a few days would pass inperfect harmony by reason of Ursula not being moved by her imp of theperverse to cut up any silly prank. Then, Iris would drink from a glassof water, to find it had been tinctured with asafetida, or brush herhair and then learn that some drops of glue had been put on the bristlesof her hairbrush.

Anger or sulks at these performances were just what Mrs. Pell wanted, soIris roared with laughter and pretended to think it all very funny,whereupon Mrs. Pell did the sulking, and Iris scored.

So it was not, perhaps, surprising that the girl concluded to leave heraunt's home and shift for herself. It would, she knew, probably meandisinheritance; but after all money is not everything, and as the oldlady grew older, her pranks became more and more an intolerablenuisance.

And Iris wanted to go out into the world and meet people. The neighborsin the small town of Berrien, where they lived, were uninteresting, andthere were few visitors from the outside world. Though less than fifteenmiles from New York, Iris rarely invited her friends to visit herbecause of the probability that her aunt would play some absurd trick onthem. This had happened so many times, even though Mrs. Pell hadpromised that it should not occur, that Iris had resolved never to tryit again.

The best friends and advisers of the girl were Mr. Bowen, the rector,and his wife. The two were also friends of Mrs. Pell, and perhaps out ofrespect for his cloth, the old lady never played tricks on the Bowens.It was their habit to dine every Sunday at Pellbrook, and the occasionwas always the pleasantest of the whole week.

The farm was a large one, about a mile from the village, and includedold-fashioned orchards and hayfields as well as more modern greenhousesand gardens. There was a lovely brook, a sunny slope of hillside, and adelightful grove of maples, and added to these a long-distance view ofhazy hills that made Pellbrook one of the most attractive country placesfor many miles around.

Ursula Pell sat on her verandah quite contentedly gazing over thelandscape and thinking about her multitudinous affairs.

"I s'pose I oughtn't to tease that child," she thought, smiling at therecollection; "I don't know what I'd do, if she should leave me! Winwent, but, land! you can't keep a young man down! A girl, now, 'sdifferent. I guess I'll take Iris to New York next winter and let herhave a little fling. I'll pretend I'm going alone, and leave her here tokeep the house, and then I'll take her too! She'll be so surprised!"

The old lady's eyes twinkled and she fairly reveled in the joke shewould play on her niece. And, not to do her an injustice, she meant noharm. She really thought only of the girl's glad surprise at learningshe was to go, and gave no heed to the misery that might be caused bythe previous disappointment.

A woman came out from the house to ask directions for dinner.

"Yes, Polly," said Ursula Pell, "the Bowens will dine here as usual.Dinner at one-thirty, sharp, as the rector has to leave at three, toattend some meeting or other. Pity they had to have it on Sunday."

There was some discussion of the menu and then Polly, the old cook,shuffled away, and again Ursula Pell sat alone.

"An actress!" she ruminated, "my little Iris an actress! Well, I guessnot! But I can persuade her out of that foolishness, I'll bet! Why, if Ican't do it any other way, I'll take her traveling,--I'll--why, I'llgive her her inheritance now, and let her amuse herself being an heiressbefore I'm dead and gone. Why should I wait for that, any way? Suppose Igive her the pin at once--I'd do it to-day, I believe, while thenotion's on me, if I only had it here. I can get it from Mr. Chapin in afew days, and then--well, then, Iris would have something to interesther! I wonder how she'd like a whole king's ransom of jewels! She's likea princess herself. And, then, too, that girl ought to marry, and marrywell. I suppose I ought to have been thinking about this before. I musttalk to the Bowens--of course, there's no one in Berrien--I did thinkone time Win might fall in love with her, but then he went away, andnow he never comes up here any more. I wonder if Iris cares especiallyfor Win. She never says anything about him, but that's no sign, one wayor the other. I'd like her to marry Roger Downing, but she snubs himunmercifully. And he is a little countrified. With Iris' beauty and thefortune I shall leave her, she could marry anybody on earth! I believeI'll take her traveling a bit, say, to California, and then spend thewinter in New York and give the girl a chance. And I must quit teasingher. But I do love to see that surprised look when I play someoutlandish trick on her!"

The old lady's eyes assumed a vixenish expression and her smile widenedtill it was a sly, almost diabolical grin. Quite evidently she was eventhen planning some new and particularly disagreeable joke on Iris.

At length she rose and went into the house to write in her diary. UrsulaPell was of most methodical habits, and a daily journal was regularlykept.

The main part of the house was four square, a wide hall running straightthrough the center, with doors front and back. On the left, as oneentered, the big living room was in front, and behind it a smallersitting room, which was Mrs. Pell's own. Not that anyone was unwelcomethere, but it held many of her treasures and individual belongings, andserved as her study or office, for the transaction of the variousbusiness matters in which she was involved. Frequently her lawyer wascloseted with her here for long confabs, for Ursula Pell was greatlygiven to the pleasurable entertainment of changing her will.

She had made more wills than Lawyer Chapin could count, and each in turnwas duly drawn up and witnessed and the previous one destroyed. Herdiary usually served to record the changes she proposed making, and whenthe time was ripe for a new will, the diary was requisitioned fordirection as to the testamentary document.

The wealth of Ursula Pell was enormous, far more so than one wouldsuppose from the simplicity of her household appointments. This was notdue to miserliness, but to her simple tastes and her frugal early life.Her fortune was the bequest of her husband, who, now dead more thantwenty years, had amassed a great deal of money which he had investedalmost entirely in precious stones. It was his theory and belief thatstocks and bonds were uncertain, whereas gems were always valuable. Hiscollection included some world-famous diamonds and rubies, and a set ofemeralds that were historic.

But nobody, save Ursula Pell herself, knew where these stones were.Whether in safe deposit or hidden on her own property, she had nevergiven so much as a hint to her family or her lawyer. James Chapin knewhis eccentric old client better than to inquire concerning thewhereabouts of her treasure, and made and remade the wills disposing ofit, without comment. A few of the smaller gems Mrs. Pell had given toIris and to young Bannard, and some, smaller still, to more distantrelatives; but the bulk of the collection had never been seen by thepresent generation.

She often told Iris that it should all be hers eventually, but Irisdidn't seriously bank on the promise, for she knew her erratic auntmight quite conceivably will the jewels to some distant cousin, in amoment of pique at her niece.

For Iris was not diplomatic. Never had she catered to her aunt's whimsor wishes with a selfish motive. She honestly tried to live peaceablywith Mrs. Pell, but of late she had begun to believe that impossible,and was planning to go away.

As usual on Sunday morning, Ursula Pell had her house to herself.

Her modest establishment

consisted of only four servants, who engagedadditional help as their duties required. Purdy, the old gardener, wasthe husband of Polly, the cook; Agnes, the waitress, also served asladies' maid when occasion called for it. Campbell, the chauffeur,completed the menage, and all other workers, and there were a good many,were employed by the day, and did not live at Pellbrook.

Mrs. Pell rarely went to church, and on Sunday mornings Campbell tookIris to the village. Agnes accompanied them, as she, too, attended theEpiscopal service.

Purdy and his wife drove an old horse and still older buckboard to asmall church nearby, which better suited their type of piety.

Polly was a marvel of efficiency and managed cleverly to go to meetingwithout in any way delaying or interfering with her preparations for theSunday dinner. Indeed, Ursula Pell would have no one around her who wasnot efficient. Waste and waste motion were equally taboo in thathousehold.

The mistress of the place made her customary round of the kitchenquarters, and, finding everything in its usual satisfactory condition,returned to her own sitting room, and took her diary from her desk.

At half-past twelve the Purdys returned, and at one o'clock the motorcar brought its load from the village.

"Well, well, Mr. Bowen, how do you do?" the hostess greeted them as theyarrived. "And dear Mrs. Bowen, come right in and lay off your bonnet."

The wide hall, with its tables, chairs and mirrors offered ampleaccommodations for hats and wraps, and soon the party were seated on thefront part of the broad verandah that encircled three sides of thehouse.

Mr. Bowen was stout and jolly and his slim shadow of a wife acted as asort of Greek chorus, agreeing with and echoing his remarks andopinions.

Conversation was in a gay and bantering key, and Mrs. Pell was in highgood humor. Indeed, she seemed nervously excited and a littlehysterical, but this was not entirely unusual, and her guests fittedtheir mood to hers.

A chance remark led to mention of Mrs. Pell's great fortune of jewels,and Mr. Bowen declared that he fully expected she would bequeath themall to his church to be made into a wonderful chalice.

"Not a bad idea," exclaimed Ursula Pell; "and one I've never thought of!I'll get Mr. Chapin over here to-morrow to change my will."

"Who will be the loser?" asked the rector. "To whom are they willed atpresent?"

"That's telling," and Mrs. Pell smiled mysteriously.

"Don't forget you've promised me the wonderful diamond pin, auntie,"said Iris, bristling up a little.

"What diamond pin?" asked Mrs. Bowen, curiously.

"Oh, for years, Aunt Ursula has promised me a marvelous diamond pin, themost valuable of her whole collection--haven't you, auntie?"

"Yes, Iris," and Mrs. Pell nodded her head, "that pin is certainly themost valuable thing I possess."

"It must be a marvel, then," said Mr. Bowen, his eyes opening wide, "forI've heard great tales of the Pell collection. I thought they were allunset jewels."

"Most of them are," Mrs. Pell spoke carelessly, "but the pin I shallleave to Iris----"

At that moment dinner was announced, and the group went to the diningroom. This large and pleasant room was in front on the right, and backof it were the pantries and kitchens. A long rear extension provided theservants' quarters, which were numerous and roomy. The house wascomfortable rather than pretentious, and though the village folkwondered why so rich a woman continued to live in such an old-fashionedhome, those who knew her well realized that the place exactly met UrsulaPell's requirements.

The dinner was in harmony with the atmosphere of the home. Plentiful,well-cooked food there was, but no attempt at elaborate confections orany great formality of service.

One concession to modernity was a small dish of stuffed dates at eachcover, and of these Mrs. Pell spoke in scornful tones.

"Some of Iris' foolishness," she observed. "She wants all sorts ofknick-knacks that she considers stylish!"

"I don't at all, auntie," denied the girl, flushing with annoyance, "butwhen you ate those dates at Mrs. Graham's the other day, you enjoyedthem so much I thought I'd make some. She gave me her recipe, and Ithink they're very nice."

"I do, too," agreed Mrs. Bowen, eating a date appreciatively, andfeeling sorry for Iris' discomfiture. For though many girls might notmind such disapproval, Iris was of a sensitive nature, and cringedbeneath her aunt's sharp words.

In an endeavor to cover her embarrassment, she picked up a date from herown portion and bit off the end.

From the fruit spurted a stream of jet black ink, which stained Iris'lips, offended her palate, and spilling on her pretty white frock,utterly ruined the dainty chiffon and lace.

She comprehended instantly. Her aunt, to annoy her, had managed toconceal ink in one of the dates, and place it where Iris would naturallypick it up first.

With an angry exclamation the girl left the table and ran upstairs.

The Deep Lake Mystery

The Deep Lake Mystery The Man Who Fell Through the Earth

The Man Who Fell Through the Earth The Mystery of the Sycamore

The Mystery of the Sycamore The Mystery Girl

The Mystery Girl Patty Blossom

Patty Blossom Patty and Azalea

Patty and Azalea The Room with the Tassels

The Room with the Tassels The Vanishing of Betty Varian

The Vanishing of Betty Varian Murder in the Bookshop

Murder in the Bookshop The Staying Guest

The Staying Guest The Curved Blades

The Curved Blades Patty—Bride

Patty—Bride The Mark of Cain

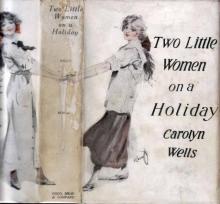

The Mark of Cain Two Little Women on a Holiday

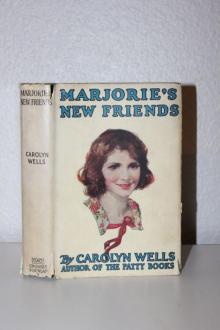

Two Little Women on a Holiday Marjorie's New Friend

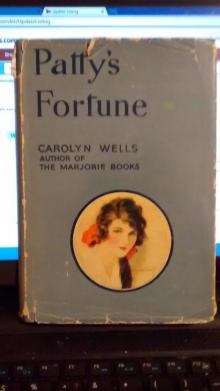

Marjorie's New Friend Patty's Fortune

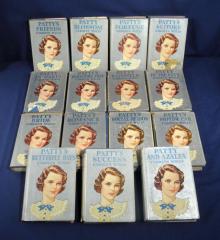

Patty's Fortune Patty's Social Season

Patty's Social Season Patty in Paris

Patty in Paris The Diamond Pin

The Diamond Pin The Come Back

The Come Back The Dorrance Domain

The Dorrance Domain Marjorie at Seacote

Marjorie at Seacote Patty's Butterfly Days

Patty's Butterfly Days Patty's Motor Car

Patty's Motor Car Patty's Success

Patty's Success Patty's Suitors

Patty's Suitors Patty's Summer Days

Patty's Summer Days Two Little Women

Two Little Women Patty Fairfield

Patty Fairfield Marjorie's Busy Days

Marjorie's Busy Days Betty's Happy Year

Betty's Happy Year In the Onyx Lobby

In the Onyx Lobby Marjorie's Maytime

Marjorie's Maytime The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK®

The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK® The Gold Bag

The Gold Bag The Clue

The Clue The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery

The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery