- Home

- Carolyn Wells

The Dorrance Domain

The Dorrance Domain Read online

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Mary Meehan and the OnlineDistributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

THE DORRANCE DOMAIN

_By_ CAROLYN WELLS

_Illustrated by_ PELAGIE DOANE

GROSSET & DUNLAP _Publishers_ NEW YORK

_Copyright, 1905_, BY W. A. WILDE COMPANY, _All rights reserved_.

The Dorrance Domain.

Made in the United States of America

"IF THAT'S THE DORRANCE DOMAIN, IT'S ALL RIGHT. WHAT DOYOU THINK, FAIRY?"]

Contents

CHAPTER PAGE

I. COOPED UP 9

II. REBELLIOUS HEARTS 22

III. DOROTHY'S PLAN 35

IV. THE DEPARTURE 48

V. THE MAMIE MEAD 60

VI. THE DORRANCE DOMAIN 73

VII. MR. HICKOX 86

VIII. MRS. HICKOX 99

IX. THE FLOATING BRIDGE 112

X. THE HICKOXES AT HOME 124

XI. SIX INVITATIONS 137

XII. GUESTS FOR ALL 149

XIII. AN UNWELCOME LETTER 161

XIV. FINANCIAL PLANS 174

XV. A SUDDEN DETERMINATION 188

XVI. A DARING SCHEME 201

XVII. REGISTERED GUESTS 214

XVIII. AMBITIONS 226

XIX. THE VAN ARSDALE LADIES 239

XX. A REAL HOTEL 252

XXI. UPS AND DOWNS 265

XXII. TWO BOYS AND A BOAT 278

XXIII. AN UNWELCOME PROPOSITION 290

XXIV. DOROTHY'S REWARD 307

The Dorrance Domain

CHAPTER I

COOPED UP

"I _wish_ we didn't have to live in a boarding-house!" said DorothyDorrance, flinging herself into an armchair, in her grandmother's room,one May afternoon, about six o'clock.

She made this remark almost every afternoon, about six o'clock, whateverthe month or the season, and as a rule, little attention was paid to it.But to-day her sister Lilian responded, in a sympathetic voice,

"_I_ wish we didn't have to live in a boarding-house!"

Whereupon Leicester, Lilian's twin brother, mimicking his sister'stones, dolefully repeated, "I wish _we_ didn't have to live in aboarding-house!"

And then Fairy, the youngest Dorrance, and the last of the quartet,sighed forlornly, "I wish we didn't have to live in a _boarding-house_!"

There was another occupant of the room. A gentle white-haired old lady,whose sweet face and dainty fragile figure had all the effects of anivory miniature, or a painting on porcelain.

"My dears," she said, "I'm sure I wish you didn't."

"Don't look like that, grannymother," cried Dorothy, springing to kissthe troubled face of the dear old lady. "I'd live here a million years,rather than have you look so worried about it. And anyway, it wouldn'tbe so bad, if it weren't for the dinners."

"I don't mind the dinners," said Leicester, "in fact I would be rathersorry not to have them. What I mind is the cramped space, and theshut-up-in-your-own-room feeling. I spoke a piece in school last week,and I spoke it awful well, too, because I just meant it. It began, 'Iwant free life, and I want fresh air,' and that's exactly what I dowant. I wish we lived in Texas, instead of on Manhattan Island. Texashas a great deal more room to the square yard, and I don't believepeople are crowded down there."

"There can't be more room to a square yard in one place than another,"said Lilian, who was practical.

"I mean back yards and front yards and side yards,--and I don't carewhether they're square or not," went on Leicester, warming to hissubject. "My air-castle is situated right in the middle of the state ofTexas, and it's the only house in the state."

"Mine is in the middle of a desert island," said Lilian; "it's so muchnicer to feel sure that you can get to the water, no matter in whatdirection you walk away from your house."

"A desert island would be nice," said Leicester; "it would be moreexciting than Texas, I suppose, on account of the wild animals. But thenin Texas, there are wild men and wild animals both."

"I like plenty of room, too," said Dorothy, "but I want it inside myhouse as well as out. Since we are choosing, I think I'll choose tolive in the Madison Square Garden, and I'll have it moved to the middleof a western prairie."

"Well, children," said Mrs. Dorrance, "your ideas are certainly bigenough, but you must leave the discussion of them now, and go to yoursmall cramped boarding-house bedrooms, and make yourselves presentableto go down to your dinner in a boarding-house dining-room."

This suggestion was carried out in the various ways that werecharacteristic of the Dorrance children.

Dorothy, who was sixteen, rose from her chair and humming a waltz tune,danced slowly and gracefully across the room. The twins, Lilian andLeicester, fell off of the arms of the sofa, where they had beenperched, scrambled up again, executed a sort of war-dance and thendashed madly out of the door and down the hall.

Fairy, the twelve year old, who lived up to her name in all respects,flew around the room, waving her arms, and singing in a high soprano,"Can I wear my pink sash? Can I wear my pink sash?"

"Yes, yes," said Mrs. Dorrance, "you may wear anything you like, ifyou'll only keep still a minute. You children are too boisterous for aboarding-house. You _ought_ to be in the middle of a desert orsomewhere. You bewilder me!"

But about fifteen minutes later it was four decorous young Dorrances whoaccompanied their grandmother to the dining-room. Not that they wantedto be sedate, or enjoyed being quiet, but they were well-bred childrenin spite of their rollicking temperaments. They knew perfectly well howto behave properly, and always did it when the occasion demanded.

And, too, the atmosphere of Mrs. Cooper's dining-room was an assistancerather than a bar to the repression of hilarity.

The Dorrances sat at a long table, two of the children on either side oftheir grandmother, and this arrangement was one of their chiefgrievances.

"If we could only have a table to ourselves," Leicester often said, "itwouldn't be so bad. But set up side by side, like the teeth in a comb,cheerful conversation is impossible."

"But, my boy," his grandmother would remonstrate, "you must learn toconverse pleasantly with those who sit opposite you. You can talk withyour sisters at other times."

So Leicester tried, but it is exceedingly difficult for a fourteen yearold boy to adapt himself to the requirements of polite conversation.

On the evening of which we are speaking, his efforts, though well meant,were unusually unsuccessful.

Exactly opposite Leicester sat Mr. Bannister, a ponderous gentleman,both physically and mentally. He was a bachelor, and his only idearegarding children was that they should be treated jocosely. He also hadhis own ideas of jocose treatment.

"Well, my little man," he said, smiling broadly at Leicester, "did yougo to school to-day?"

As he asked this question every night at dinner, not even exceptingSaturdays and Sundays, Leicester felt justified in answering only, "Yes,sir."

"That's nice; and what did you learn?"

As this question invariably followed the other, Leicester was not whollyunprepared for it. But the discussion of air-castles in Texas, or on aprairie, had made the boy a little impatient o

f the narrow dining-room,and the narrow table, and even of Mr. Bannister, though he was by nomeans of narrow build.

"I learned my lessons," he replied shortly, though there was no rudenessin his tone.

"Tut, tut, my little man," said Mr. Bannister, playfully shaking a fatfinger at him, "don't be rude."

"No, sir, I won't," said Leicester, with such an innocent air ofaccepting a general bit of good advice, that Mr. Bannister was quitediscomfited.

Grandma Dorrance looked at Leicester reproachfully, and Mrs. Hill, whowas a sharp-featured, sharp-spoken old lady, and who also sat on theother side of the table, said severely, to nobody in particular,"Children are not brought up now as they were in my day."

This had the effect of silencing Leicester, for the three olderDorrances had long ago decided that it was useless to try to talk toMrs. Hill. Even if you tried your best to be nice and pleasant, she wassure to say something so irritating, that you just _had_ to lose yourtemper.

But Fairy did not subscribe to this general decision. Indeed, Fairy'schief characteristic was her irrepressible loquacity. So much troublehad this made, that she had several times been forbidden to talk at thedinner-table at all. Then Grandma Dorrance would feel sorry for thedolefully mute little girl, and would lift the ban, restricting her,however, to not more than six speeches during any one meal.

Fairy kept strict account, and never exceeded the allotted number, butshe made each speech as long as she possibly could, and rarely stoppeduntil positively interrupted.

So she took it upon herself to respond to Mrs. Hill's remark, and atthe same time demonstrate her loyalty to her grandmother.

"I'm sure, Mrs. Hill," Fairy began, "that nobody could bring up childrenbetter than my grannymother. She is the best children bring-upper in thewhole world. I don't know how your grandmother brought you up,--orperhaps you had a mother,--some people think they're better thangrandmothers. I don't know; I never had a mother, only a grandmother,but she's just the best ever, and if us children aren't good, it's ourfault and not hers. She says we're boist'rous, and I 'spect we are. Mr.Bannister says we're rude, and I 'spect we are; but none of theseobjectionaries is grandma's fault!" Fairy had a way of using long wordswhen she became excited, and as she knew very few real ones she oftenmade them up to suit herself. And all her words, long or short came outin such a torrent of enthusiasm and emphasis, and with such a degree ofrapidity that it was a difficult matter to stop her. So on she went. "Soit's all right, Mrs. Hill, but when we don't behave just first-rate, orjust as children did in your day, please keep a-remembering to blame usand not grandma. You see," and here Fairy's speech assumed aconfidential tone, "we don't have room enough. We want free life and wewant fresh air, and then I 'spect we'd be more decorious."

"That will do, Fairy," said Mrs. Dorrance, looking at her gravely.

"Yes'm," said Fairy, smiling pleasantly, "that'll do for one."

"And that makes two! now you've had two speeches, Fairy," said herbrother, teasingly.

"I have not," said Fairy, "and an explanationary speech doesn't count!"

"Yes, it does," cried Lilian, "and that makes three!"

"It doesn't, does it, grandma?" pleaded Fairy, lifting her big blue eyesto her grandmother's face.

Mrs. Dorrance looked helpless and a little bewildered, but she onlysaid, "Please be quiet, Fairy; I might like to talk a little, myself."

"Oh, that's all right, grandma dear," said Fairy, placidly; "I know howit is to feel conversationary myself."

The children's mother had died when Fairy was born, and her father hadgiven her the name of Fairfax because there had always been a FairfaxDorrance in his family for many generations. To be sure it had alwaysbefore been a boy baby who was christened Fairfax, but the only boy inthis family had been named Leicester; and so, one Fairfax Dorrance was agirl. From the time she was old enough to show any characteristics atall, she had been fairy-like in every possible way. Golden hair, bigblue eyes and a cherub face made her a perfect picture of child beauty.Then she was so light and airy, so quick of motion and speech, and soimmaculately dainty in her dress and person, that Fairy seemed to be theonly fitting name for her. No matter how much she played rollickinggames, her frock never became rumpled or soiled; and the big white bowwhich crowned her mass of golden curls always kept its shape andposition even though its wearer turned somersaults. For Fairy was by nomeans a quiet or sedate child. None of the Dorrances were that. And theyoungest was perhaps the most headstrong and difficult to control. Butthough impetuous in her deeds and mis-deeds, her good impulses wereequally sudden, and she was always ready to apologize or make amends forher frequent naughtiness.

And so after dinner, she went to Mrs. Hill, and said with a mostengaging smile, "I'm sorry if I 'fended you, and I hope I didn't. Yousee I didn't mean to speak so much, and right at the dinner table, too,but I just _have_ to stand up for my grannymother. She's so old, and soladylike that she can't stand up for herself. And I was 'fraid youmightn't understand, so I thought I'd 'pologize. Is it all right?"

Fairy looked up into Mrs. Hill's face with such angelic eyes andpleading smile, that even that dignified lady unbent a little.

"Yes, my dear," she said; "it's all right for you to stand up for yourgrandmother, as you express it. But you certainly do talk too much forsuch a little girl."

"Yes'm," said Fairy, contritely, "I know I do. It's my upsetting sin;but somehow I can't help it. My head seems to be full of words, and theyjust keep spilling out. Don't you ever talk too much, ma'am?"

"No; I don't think I do."

"You ought to be very thankful," said Fairy, with a sigh; "it is anawful affliction. Why once upon a time----"

"Come, Fairy," said Mrs. Dorrance; "say good-night to Mrs. Hill, andcome up-stairs with me."

"Yes, grandma, I'm coming. Good-night, Mrs. Hill; I'm sorry I have to gojust now 'cause I was just going to tell you an awful exciting story.But perhaps to-morrow----"

"Come, Fairy," said Mrs. Dorrance; "come at once!" And at last thegentle old lady succeeded in capturing her refractory granddaughter, andled the dancing sprite away to her own room.

The Deep Lake Mystery

The Deep Lake Mystery The Man Who Fell Through the Earth

The Man Who Fell Through the Earth The Mystery of the Sycamore

The Mystery of the Sycamore The Mystery Girl

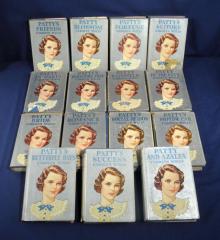

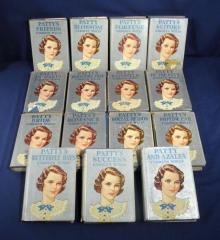

The Mystery Girl Patty Blossom

Patty Blossom Patty and Azalea

Patty and Azalea The Room with the Tassels

The Room with the Tassels The Vanishing of Betty Varian

The Vanishing of Betty Varian Murder in the Bookshop

Murder in the Bookshop The Staying Guest

The Staying Guest The Curved Blades

The Curved Blades Patty—Bride

Patty—Bride The Mark of Cain

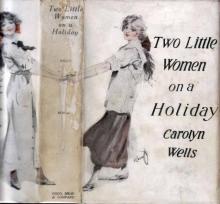

The Mark of Cain Two Little Women on a Holiday

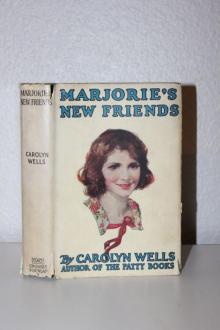

Two Little Women on a Holiday Marjorie's New Friend

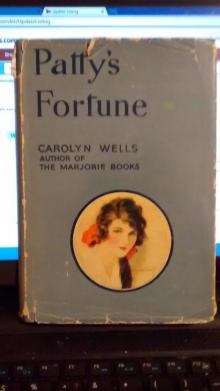

Marjorie's New Friend Patty's Fortune

Patty's Fortune Patty's Social Season

Patty's Social Season Patty in Paris

Patty in Paris The Diamond Pin

The Diamond Pin The Come Back

The Come Back The Dorrance Domain

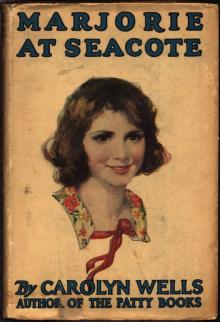

The Dorrance Domain Marjorie at Seacote

Marjorie at Seacote Patty's Butterfly Days

Patty's Butterfly Days Patty's Motor Car

Patty's Motor Car Patty's Success

Patty's Success Patty's Suitors

Patty's Suitors Patty's Summer Days

Patty's Summer Days Two Little Women

Two Little Women Patty Fairfield

Patty Fairfield Marjorie's Busy Days

Marjorie's Busy Days Betty's Happy Year

Betty's Happy Year In the Onyx Lobby

In the Onyx Lobby Marjorie's Maytime

Marjorie's Maytime The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK®

The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK® The Gold Bag

The Gold Bag The Clue

The Clue The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery

The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery