- Home

- Carolyn Wells

The Diamond Pin Page 14

The Diamond Pin Read online

Page 14

CHAPTER XIV

FIBSY AND SAM

"There are two things to find," Fleming Stone said, "the murderer andthe pin. There are two things to find out, how the murderer got away,and why the pin is valuable."

Stone persisted in his belief that the pin was of value, and that insome way it would lead to the discovery of the jewels. He had read allof Ursula Pell's diary, and though it gave no definite assurance, therewere hints in it that strengthened his theory. Before he had been in thePell house twenty-four hours, he had learned all he could from theexamination of the whole premises and the inspection of all the papersand books in Mrs. Pell's desk. He declared that the murderer was afterthe pin, and that, failing to find it, he had maltreated Ursula Pell ina fit of rage at his failure.

"She was of an irritating nature, you tell me," Stone said, "and it maywell be that she not only refused to give up the pin, but teased andtantalized the intruder who sought it."

"But what use _could_ the pin be as a clue to the jewels?" LucilleDarrel asked. "I can't imagine any theory that would explain that."

"I can imagine a theory," Stone responded, "but it is merely a theory--asurmise, rather; and it is so doubtful, at best, I'd rather not divulgeit at present. But the pin must be found."

"I haven't found it, but I've a notion of which way to look," saidFibsy, who had just entered the room.

It was Mrs. Pell's sitting room, and Fleming Stone was still fingeringsome packets of papers in the desk.

"Out with it, Fibs, for I'm going over to see Mr. Bannard now, and Iwant all your information before I go."

So Fibsy told of what Sam had said, and of the snatch of song he hadsung.

"Good enough as far as it goes," commented Stone, "but your source ofknowledge seems a bit uncertain."

"That's just it," said Fibsy. "That's why I didn't tell you this lastnight. I thought I'd tackle friend Boobikins this morning and see if Icould get more of the real goods. But, nixie. Sam says he has the pin,but he doesn't know where it is."

"I'm afraid you're trying to draw water from an empty well, son; bettertry some other green fields and pastures new."

"I know it, Mr. Stone, but s'pose you just speak to the innocent beforeyou go away. You can tell if he knows anything."

"Why should Sam steal the pin?" Iris asked, her eyes big with amazement.

"You can't tell _what_ such people will do," Fibsy returned. "He mayhave seen you hiding it, as he says he did, and he may have come in andstolen it, just because of a mere whimsey in his brain. Is he aroundhere much?"

"Quite a good deal, of late. He's fond of Agnes, and he trails herabout, like a dog after its master. Aunt Ursula wouldn't have him aroundmuch when she was here, but Miss Darrel doesn't mind."

"I don't like him," said Lucille, "but I am sorry for him, and he doesadore Agnes. I think he ought to be put in an institution."

"Oh, no," said Iris, "he isn't bad enough for that. He's not reallyinsane, just feeble-minded. He's perfectly harmless."

"Bring him in here," suggested Stone.

Fibsy ran out, and came back with the half-witted boy.

"Hello, Sam," said Stone, in an off-handed, kindly way, "you're the boyfor us. Now, where did you say you found that pin?"

"Here," and Sam pushed his hand down in the big chair, in the very spotwhere Iris had concealed it.

"Good boy! How'd you get in this room?"

"Through window in other room--walked in here!" He spoke with pride inhis achievement. But at Stone's next question, a look of deep cunningcame into his eyes, and he shook his head. For the detective said,"Where is the pin now, Sam?"

The lack-luster eyes gleamed with an uncanny wisdom, and the stupid faceshowed a stubborn denial, as he said, "I donno, I donno, I donno."

And then he broke forth again into the droning song:

"It is a sin to steal a pin, As well as any greater thing!"

This couplet he repeated, in his peculiarly insistent way, until theywere all nearly frantic.

"Stop that!" ordered Lucille. "Put him out of the room, somebody. Hushup, Sam!"

"Wait a minute," said Stone, "listen, Sam, what will you take to show mewhere the pin is?"

"Dollars, dollars--a lot of dollars!"

"Two?" and Stone drew out his wallet.

"Yes, 'two, three, four--lot of dollars!"

"And then you'll tell us where the pin is?"

"Yes, Sam tell then--it is a sin----"

"Don't sing that again. Look, here's four nice dollar bills; now where'sthe pin?"

"Where?" Sam looked utterly blank. "Where's the pin? Nice pin, oh,pinny, pin, pin! Where's the pin? Oh, _I_ know!"

"All right, where?"

"Forgot! All forgot. Nice pin forgot--forgot--forgot----"

"Oh, pshaw!" exclaimed Lucille, "he doesn't know anything! I don'tbelieve he really took the pin at all. He heard Agnes and Polly talkingabout it and he thinks he did."

"Oh, yes, Sam took pin!" declared the idiot boy, himself. "Yes, Sam tookpin--pinny-pin--beautiful day, beautiful day, beautiful--beautiful day!"

The boy stood babbling. He was not ill-looking, and the pathos of it allmade him far from ridiculous. A tall, well-formed lad, his face wouldhave been really attractive, had the light of intelligence blessed it.

But his blue eyes were vacant, his lips were not firm, and his headturned unsteadily from side to side. Yet, now and again, a gleam ofcunning showed in his expression, and Fibsy, watching such moments,tried to make him speak rationally.

"Think it up, Sam," he said, kindly. "There! You remember now! So youdo! Where did you put the nice pin?"

"In the crack of the floor! In the crack of the floor! In the----"

"Yes, of course you did!" encouraged Stone. "That was a good place. Now,what floor was it? This room?"

"No, oh, nony no! Not this floor, no, no, no--'nother floor."

But all further effort to learn what floor was unsuccessful. Indeed,they didn't really think the boy had hidden the pin in a floor crack, orat least they could not feel sure of it.

"He never had the pin at all," Lucille asserted, "he heard the otherstalking about it, probably they said it might be in a crack, and heremembered the idea."

"Keep him on the place," Stone told them, as he prepared to go to seeBannard. "Don't let Sam get away, whatever you do."

* * * * *

The call on Winston Bannard was preceded by a short visit to DetectiveHughes.

While the lesser detective was not annoyed or offended at Stone'staking up the case, yet it was part of his professional pride to be ableto tell his more distinguished colleague any new points he could gethold of. And, to-day, Hughes had received back from a local handwritingexpert the letter that had been sent to Iris.

"And he says," Hughes told the tale, "he says, Barlow does, that thatletter is in Win Bannard's writing, but disguised!"

"What!" and Stone eyed the document incredulously.

"Yep, Barlow says so, and he's an expert, he is. See, those twirly y'sand those extra long-looped g's are just like these here in a lot ofletters of Bannard's."

"Are these in Bannard's writing?"

"Yes, those are all his. You can see from their contents. Now, this herenote signed William Ashton has the same peculiarities."

"Yes, I see that. Do you believe Bannard wrote this letter to hiscousin?"

"She ain't exactly his cousin, only a half way sort of one."

"I know; never mind that now. Do you think Bannard wrote the note?"

"Yes, I do. I believe Win Bannard is after that pin, so's he can findthem jewels----"

"Oh, then you think the pin is a guide to the jewels?"

"Well, it must be, as you say so. 'Tenny rate, the murderer wantedsomething, awful bad. It never seemed like he was after just money, orhe'd 'a' come at night, don't you think so?"

"Perhaps."

"Well, say it was Win, there's nothing to offset that theory. Andeverything to point toward it.

Moreover, there's no other suspect."

"William Ashton? Rodney Pollock?"

"All the same man," opined Hughes, "and all--Winston Bannard!"

"Oh, I don't know----"

"How you going to get around that letter? Can't you see yourself it'sBannard's writing disguised? And not very much disguised, at that. Why,look at the capital W! The one in William and this one in his ownsignature are almost identical."

"Why didn't he try to disguise them?"

"He did disguise the whole letter, but he forgot now and then. Theyalways do. It's mighty hard, Barlow says, to keep up the disguise allthrough. They're sure to slip up, and return to their natural formationof the letters here and there."

"I suppose that's so. Shall I confront Bannard with this?"

"If you like. You're in charge. At least, I'm in with you. I don't wantto run counter to your ideas in any way."

"Thank you, Mr. Hughes. I appreciate the justice and courtesy of yourattitude toward me, and I thank you for it."

"But it don't extend to that boy--that cub of yours!"

"Terence?" Fleming Stone laughed. "All right, I'll tell him to keep outof your way. He'll not bother you, Mr. Hughes."

"Thank you, sir. Shall I go over to the jail with you?"

"No, I'd rather go alone. But as to this theory of yours. You blameBannard for all the details of this thing? Do you think he kidnappedMiss Clyde last Sunday?"

"I think it was his doing. Of course, the two people who carried her offwere merely tools of the master mind. Bannard could have directed themas well as anybody else."

"He could, surely. Now, here's another thing--I want to trace the housewhere Miss Clyde was taken. Seems to me that would help a lot."

"Lord, man! How can you find that?"

"Do you know any nearby town where there's an insurance agent namedClement Foster?"

"Sure I do; he lives over in Meadville."

"Then Meadville is very likely the place where that house is."

"How do you know?"

"I don't _know_. But I asked Miss Clyde to think of anything in the roomshe was in that might be indicative, and she told of a calendar withthat agent's name on it. It's only a chance, but it is likely that thecalendar was in the same town that the agent lives and works in."

"Of course it is! Very likely! You _are_ a smart chap, ain't you!"

Mr. Hughes' admiration was so full and frank that Stone smiled.

"That isn't a very difficult deduction," he said, "but we must verifyit. This afternoon, we'll drive over there with Miss Clyde, and see ifwe can track down the house we're after."

* * * * *

Fleming Stone went alone to his interview with Winston Barnard. He foundthe young man willing to talk, but hopelessly dejected.

"There's no use, Mr. Stone," he said, after some roundaboutconversation, "I'll be railroaded through. I didn't kill my aunt, butthe circumstantial evidence is so desperately strong against me thatnobody will believe me innocent. They can't prove it, because they can'tfind out how I got in, or rather out, but as there's nobody else tosuspect, they'll stick to me."

"How _did_ you get out?"

"Not being in, I didn't get out at all."

"I mean when you were there in the morning!"

Winston Bannard turned white and bestowed on his interlocutor a glanceof utter despair.

"For Heaven's sake!" he exclaimed, "you've been in Berrien less than twodays, and you've got that, have you?"

"I have, Mr. Bannard, and before we go further, let me say that I amyour friend, and that I do not think you are guilty of murder or oftheft."

"Thank you, Mr. Stone," and Bannard interrupted him to grasp his hand."That's the first word of cheer I've had! My lawyer is a half-heartedchampion, because he believes in his soul that I did it!"

"Have you told him the whole truth?"

"I have not! I couldn't! Every bit of it would only drag me deeper intothe mire of inexplicable mystery."

"Will you tell it all to me?"

"Gladly, if you'll promise to believe me."

"I can't promise that, blindly, but I'll tell you that I think I Shallbe able to recognize the truth as you tell it. Did you write the lettersigned William Ashton?"

"Lord, no! Why would I do that?"

"To get the pin----"

"Now, hold on, before we go further, Mr. Stone, do satisfy my curiosity.Is that pin, that foolish, common little pin of any value?"

"I think so, Mr. Bannard. I can't tell until I see it----"

"But man, why _see_ it? It's just like any common pin! I examined itmyself, and it isn't bent or twisted, or different in any way frommillions of other pins."

"Quite evidently then, you've not tried to get possession of it. Yourscorn of it is sincere, I'm certain."

"You may be! I've no interest in that pin, for I know it was only a fooljoke of Aunt Ursula's to tease poor little Iris."

"Her joking habit was most annoying, was it not?"

"All of that, and then some! She was a terror! Why, I simply couldn'tkeep on living with her. She made my life a burden. And she did the sameby Iris. What that girl has suffered! But the last straw was the worst.Why, for years and years Aunt Ursula told of the valuable diamond pinshe had bequeathed to Iris; at least, we thought she said diamond pin,but she said dime an' pin, I suppose."

"Yes, I know all about that; it _was_ a cruel jest, unless--as Ihope--the pin is really of value. But never mind that now. Tell me yourstory of that fatal Sunday."

"Here goes, then. I was out with the boys the night before, and I lost alot of money at bridge. I was hard up, and I told one of the fellows I'dcome up to Berrien the next day and touch Aunt Ursula for a present. Sheoften gave me a check, if I could catch her in the right mood. So, nextday, Sunday morning, I started on my bicycle and came up here."

"What time did you leave New York?"

"'Long about nine, I guess. It was a heavenly day, and I dawdled some,for I wanted to get here after Iris had gone to church. I wanted to seeAunt Ursula alone, and then if I got the money, I wanted to go back toNew York and not spend the day here."

"Pardon this question--are you in love with Miss Clyde?"

"I am, Mr. Stone, but she doesn't care for me. She thinks me ane'er-do-well, and perhaps I am, but truly, I had turned over a newleaf and, if Iris would have smiled on me, I was going to live rightever after. But I knew she wasn't overanxious to see me, so I planned tomake my call at Pellbrook and get away while she was absent at church."

"You reached the house, then, after Miss Clyde had gone?"

"Yes, and the servants had all gone; at least, I didn't see any of them.I went in at the front door, and I found Aunt Pell in her ownsitting-room. She was glad to see me, she was in a very amiable mood,and when I asked her for some money, she willingly took her check-bookand drew me a check for five thousand dollars. I was amazed, for I hadexpected to have to coax her for it."

"And then?"

"Then I stayed about half an hour, not longer, for Aunt Ursula, thoughkind enough, seemed absent-minded, or rather, wrapped in her ownthoughts, and when I said I'd be going, she made no demur, and I went."

"At what time was this?"

"I've thought the thing over, Mr. Stone, and though I'm not positive Ithink I reached Pellbrook at quarter before eleven and left it aboutquarter after eleven."

"Leaving your aunt perfectly well and quite as usual?"

"Yes, so far as I know, save that, as I told you, she was preoccupied inher manner."

"You had a New York paper?"

"Yes, a _Herald_."

"Where did you buy it?"

"Nowhere. I have one left at my door every morning. I read it before Ileft my rooms, but I put part of it in my pocket, as I usually do, incase I wanted to look at it again."

"You know there was a _Herald_ found in the room after the murder?"

"Of course I do, but it was not mine."

"What became of yours?"

&

nbsp; "I haven't the least idea, I never thought of it again."

"Quite a coincidence, that a _Herald_ should have been left there whenyour aunt took quite another New York paper!"

"I'm telling you this thing just as it happened, Mr. Stone."

Bannard spoke sternly, and with such a straightforward glance thatFleming Stone said, "I beg your pardon--proceed."

"I went down to New York," Bannard resumed, "and I stopped at the RedFox Inn for lunch."

"At what time?"

"About noon, or a bit later. I don't know these hours exactly for I hadno notion I'd be called to account for them, and I paid little heed tothe time. I had the money I wanted, Aunt Ursula had given it to mewillingly, I could pay off my debts, and I meant then to live a lesshaphazard life. I was making all sorts of plans to make good, and sogain Iris Clyde's favor, and perhaps, later, her love. I've not told herof this, for next thing I knew, I was suspected of killing my aunt!"

"But I'm told that the detectives have inquired, and the waiter whoserved you at the inn, says you were on your way _toward_ Berrien, not_from_ it."

"Then that waiter lies. I was on my way back to New York. I lunched atthe inn, and proceeded on my way. I reached town about three or later,and when I finally got back to my rooms, I found a telegram from Iris tocome right up here. I did so, and the rest of my story is publicinformation. Now, the murderer, whoever he may have been, came to thehouse long after I left it. Oh, I can't say that, for he may have beenhidden in the house when I was there. But, anyway, he killed Aunt Ursulaabout the middle of the afternoon, so I supposed my true story would besufficient alibi. But it hasn't proved so, and now, if they say the Innpeople declare I was coming north instead of going south, as I was,then I can only say that the villain who did the deed is trying to makeit seem to have been me."

"That's my belief," agreed Stone; "the whole affair is a carefullyplanned and deep-laid scheme, and concocted in a clever and diabolicallyingenious brain."

The Deep Lake Mystery

The Deep Lake Mystery The Man Who Fell Through the Earth

The Man Who Fell Through the Earth The Mystery of the Sycamore

The Mystery of the Sycamore The Mystery Girl

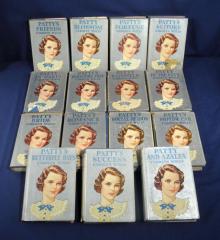

The Mystery Girl Patty Blossom

Patty Blossom Patty and Azalea

Patty and Azalea The Room with the Tassels

The Room with the Tassels The Vanishing of Betty Varian

The Vanishing of Betty Varian Murder in the Bookshop

Murder in the Bookshop The Staying Guest

The Staying Guest The Curved Blades

The Curved Blades Patty—Bride

Patty—Bride The Mark of Cain

The Mark of Cain Two Little Women on a Holiday

Two Little Women on a Holiday Marjorie's New Friend

Marjorie's New Friend Patty's Fortune

Patty's Fortune Patty's Social Season

Patty's Social Season Patty in Paris

Patty in Paris The Diamond Pin

The Diamond Pin The Come Back

The Come Back The Dorrance Domain

The Dorrance Domain Marjorie at Seacote

Marjorie at Seacote Patty's Butterfly Days

Patty's Butterfly Days Patty's Motor Car

Patty's Motor Car Patty's Success

Patty's Success Patty's Suitors

Patty's Suitors Patty's Summer Days

Patty's Summer Days Two Little Women

Two Little Women Patty Fairfield

Patty Fairfield Marjorie's Busy Days

Marjorie's Busy Days Betty's Happy Year

Betty's Happy Year In the Onyx Lobby

In the Onyx Lobby Marjorie's Maytime

Marjorie's Maytime The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK®

The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK® The Gold Bag

The Gold Bag The Clue

The Clue The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery

The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery