- Home

- Carolyn Wells

In the Onyx Lobby Page 13

In the Onyx Lobby Read online

Page 13

CHAPTER XIII

Motives

"I've got to speak, Ricky," Miss Prall said, but her tone was not angrynow. She seemed to have changed her mood and was half frightened, halfsad. "I've got to speak, to save myself. Don't you see that if thatpaper-cutter points towards me,--as Mr Gibbs implies, I must tell what Iknow----"

"What you know," assented Bates, "but not what you suspect."

"Yes, ma'am, what you suspect," directed the detective. "The time hascome, Miss Prall, when suspicions must be voiced, whether true or not,in order that we may prove or disprove them."

"Then get up your own suspicions," cried Bates. "Find your own suspectsand prove their guilt or innocence."

"We're doing that," Gibbs said, quietly, "but we necessarily depend alsoon the statements of witnesses."

"But Miss Prall isn't a witness."

"Not an eye-witness, perhaps, but a material witness, if she knowsanything that we want to know."

"She doesn't know anything you want to know," exclaimed Eliza Gurney,coming into the room. "But Kate Holland does! If you're anxious forinformation get that girl and quiz her!"

"Hush up, Eliza," stormed Letitia. "What did you learn in at theEverett's, Mr Gibbs?"

"I learned that you said you'd kill Sir Herbert Binney yourself, if youwere sure you wouldn't be found out."

"What!" Miss Prall turned perfectly white, but whether with rage orfear, Gibbs didn't know. "She said that! The little devil! Just let meget at her, once!"

"Didn't you make that remark?"

"I did not; but she did, and then, I said I would, too. Neither of usmeant it, really, but that's what was said. The woman is so clever itmakes her doubly dangerous!"

"But it's a queer thing for two ladies to be talking about killinganybody."

"Nonsense! It's done all the time. It doesn't mean they'd really doit--though sometimes I have thought----"

"Aunt Letty!" put in Bates, beseechingly.

"I will speak, Richard! Sometimes I have thought that Adeline Everettwould be capable of--of anything! Those sleek, fat, complacent peopleare the very worst sort! I bluster out frankly, but that oily, deceitfulwoman,--and that Kate of hers,--well, if you want to know mysuspicions,--there they are."

"Then, Miss Prall," Gibbs looked straight at her, "here's the situation.Both you and Mrs Everett expressed a willingness to kill Sir HerbertBinney,--no matter if it was not meant. Both of you may be said to havehad a motive; both of you could have found opportunity. And, finally,each of you claims to suspect the other. Now, granting for argument'ssake that one of you is guilty, would not the plausible procedure be topretend to suspect the other?"

"Of course it would," Eliza Gurney declared. "And since Mrs Everett isthe guilty party,--I see it all now! She casts suspicion toward MissPrall! Of course, Mrs Everett didn't do it herself, but that KateHolland did! She is a fiend incarnate, without heart or soul! Sheis----"

"There, there, Eliza, you'd better be still," Miss Prall warned her. "Ifyou go on like that, Mr Gibbs will think you're protesting too much!"

As a matter of fact, that's just what Gibbs was thinking, and he lookedsharply at Letitia, marveling at her cleverness. If she had beeninstrumental in the death of Sir Herbert, surely this was just the wayshe would conduct herself. She was deep as well as clever, and Gibbsbegan to see light.

He was convinced now that the criminals were of a more subtle type thanyoung girls in their teens could possibly be, and the affair, to histhinking, was narrowed down to the households of these two women whowere each other's enemies.

He reasoned that the only way to learn anything from such dissemblers asthey all were, was to catch them off their guard, and he greatly desiredto get the rival factions together, in order that anger or spite mightcause one or other to disclose her secret.

"Perhaps," Gibbs said, "it might be well for us to go to Mrs Everett, orsend for her to come here, and so get the testified statement as tothese assertions of willingness to kill. I don't think they're customaryamong the women of your class."

"You doubt my word!" flared up Letitia Prall. "Let me tell you, MrGibbs, that I refuse to have it corroborated by that woman! I tell youthe truth,--she is incapable of that!"

"That's why I want to give you a chance to refute her, to deny her toher face----"

"Never! I don't want to see her! She shall not enter my door! Her verypresence is contaminating! Adeline Everett! She is a slanderer----"

"Wait a moment, Miss Prall. What she has said of you, you have also saidof her!"

"But I speak truth; she tells falsehoods. Nobody ever believes a wordshe says!"

"Of course not!" chimed in Eliza. "Adeline Everett is a whitedsepulcher,--a living lie!"

Even more belligerent than the words was the tone and the facialexpression of the speaker. Miss Gurney was not a beautiful woman atbest, and her rage transformed her into a veritable termagant. Hersparse gray hair fell in wisps about her ears and her head shook inemphasis of her objurgations, while her pale blue eyes blinked with furyas she strove to find words harsh enough.

"Eliza!" and Miss Prall's warning tone was quiet but very stern. "Stopthat! You only make matters worse by going on so! If you can't keepstill, leave the room."

Eliza sniffed, but ceased her talk for the moment, at least.

"Now, Miss Prall," Gibbs resumed, "it is necessary, in my opinion, tohave an interview at which both yourself and Mrs Everett are present. Ihave a right to ask this, and I offer you the choice of going there, orsending for her to come here."

"I won't do either," snapped Letitia. "I refuse to go to her home, and Icertainly shall not let her enter mine."

"But, don't you see that is most damaging to your own side of thestory."

"What do I care? Don't think you can frighten me, young man! LetitiaPrall is quite able to take care of herself."

"That may be, but you are not able to defy, successfully, the course ofthe law. If I insist on this interview, I think, Miss Prall, you will beobliged to consent."

"And if I refuse?"

"Then, I am sorry to tell you, your refusal must be set aside, and youwill, I am sure, see the advisability of accepting the situation."

"Oh, come, Auntie," said Bates, "you're making a lot of unnecessarytrouble. Neither you nor Mrs Everett had any hand in this murder,--themere idea is ridiculous! and if you have the interview Mr Gibbs wants,it will soon be over and then you will both be freed from suspicion andcan go on with your silly 'feud.' That is a foolish thing, but trivial.This other matter is serious. You _must_ get it over with at once,--forall our sakes."

"I won't." And Miss Prall set her lips obstinately.

Gibbs rose abruptly and left the room.

"He's gone for Mrs Everett," said Richard, looking severely at his aunt."Now, you must be careful, Aunt Letty. If you don't look out, they'llaccuse you of the murder, and though you'll disprove it, it will mean awhole lot of trouble for us all."

Letitia Prall adored her nephew, and, too, she saw there was no use oftrying to avoid the meeting with Mrs Everett. It was bound to be broughtabout, sooner or later, by the determined Gibbs, and it might as well begone through with.

She sat still, thinking what attitude it was best to assume, and shedecided on continued silence.

"Eliza," she warned, "don't talk too much. You'll get us in an awfulpredicament if you're so free with your tongue. First thing you know,you'll tell----"

"Hush, they're coming!" and in a moment Gibbs rang the bell.

Richard admitted him, and with him came both Adeline Everett and themaid, Kate.

"I didn't invite your servant," was Miss Prall's only word of greeting,accompanied by a scathing glance at Kate.

"You didn't invite me," Mrs Everett returned, pertly, "and I shouldn'thave come if you had, except that I was commanded to appear by arepresentative of the law. I don't see, though, why I should be mixed upin your murder case."

"It isn't my murder case any more than it is yours, Adeline Everett,"her en

emy faced her. "I understand you're suspected of being----"

"Oh, don't, Aunt Letitia," begged Richard, who was always distressed ifobliged to be present when the two "got going," as Eliza called it."Now, please, auntie,--please, Mrs Everett, can't you two forget yourprivate enmity for a few minutes and just settle this big matter? Disarmthe suspicions of Mr Gibbs by telling the truth, by stating where youall were at the time of the murder, and so, get yourselves out of alltouch with it. Truly, you will be sorry if you don't. You don't realizewhat it will mean if you have to be mixed up in all sorts of witnessstands and things."

"Go ahead, Mr Gibbs," and Miss Prall glared at the detective. "We owethis unpleasant scene to you,--make it as short as possible."

"I will," and Gibbs' sharp eyes darted from one face to another, forthis was his harvest time, and though he expected to learn little fromthe wily women's speech, he hoped for much from their uncontrollableoutbursts of anger or their involuntary admissions.

It was a strange gathering. Letitia Prall sat on a straight-backedchair, erect and still; but looking like a leashed tiger, ready tospring.

Beside her, trying hard to keep quiet, was Eliza Gurney, small, pale,and with a distracted face and angry eyes that darted venomous glancesat the visitors.

Mrs Everett had chosen for her role an amused superiority, knowing itwould irritate Letitia Prall more than any other manner. She smiled andquickly suppressed it, she stared and then dropped her eyes and shewould impulsively begin to say something and then discreetly pause.

All this Gibbs took in and Richard, seeing the detective's interest,became alarmed. He felt sure there was something sinister concealed inthe minds of some or all of the women present and his heart sank at thepossible outcome of things.

It was inconceivable that his aunt was in any way concerned in themurder, yet it was even worse to imagine the mother of Dorcas mixed upin it. Of course, it couldn't be that either of them was reallyimplicated, but he had to recognize the fact that Gibbs was sufficientlyconvinced of such implication to call this confab.

And it was a confab. The detective did not ask direct questions, butrather brought out voluntary remarks by adroitly suggesting them.

"Now, that paper-knife----" he began, musingly.

"Is what they call a clue," said Mrs Everett. "I know nothing of suchthings,--I can't bear detective stories, but if a paper-knife was usedto kill somebody, I should think the owner of the weapon must be more orless suspected."

"Of course you think that, because you're suspected yourself," saidLetitia, coldly; "naturally you think you can cast suspicion toward me,but you can't, Adeline Everett! I gave that paper-cutter to Sir Herbertto get it mended----"

"Oho! Is _that_ the story you've trumped up! Clever, my dear, but toothin. Can't you see, Mr Gibbs, that that is a made-up yarn? She knowsSir Herbert can't deny it, and no one else can. So she thinks she'ssafe!"

"Well, she isn't," and Kate Holland gave Miss Prall a triumphant glare."That knife will hang her yet! She not only tried to make up a plausiblestory about the thing, but she tried to fasten the guilt on me by sayingI have surgical skill! Ha, ha,--because I took a nurse's training,--I'mto be suspected of murder! A fine how-do-you-do! Let me tell you, MissPrall, you overreached yourself! I've been to see Dr Pagett about it,and he says that while the fatal stroke may have been delivered bysomebody who knew just where to strike, yet, on the other hand, it mighthave been the merest ignoramus, who chanced to strike the vital point!So, your ladyship, your scheme to inculpate _me_ falls through!"

Gibbs listened eagerly, gathering the news of Dr Pagett's decision, andlearning, too, that this maid of Mrs Everett's was of a far highermentality than the average servant.

"I scorn to reply," Miss Prall said, looking over the head of thetriumphant Kate. "I do not converse with servants."

"Perhaps it would be well to dismiss both my servant and yours," drawledMrs Everett, maliciously. "Let Kate and Eliza both leave the room."

"I'm no servant!" cried Miss Gurney, bristling; "I'm Miss Prall'scompanion, quite her equal----"

"And think yourself her superior," interrupted Mrs Everett, with hermost annoying chuckle. "Well, Eliza, I look upon you as just as much aservant as my Kate,--more so, indeed, for you can't hold a candle toKate for intelligence, education or----"

"Or viciousness," Letitia broke in. "Now, Mr Gibbs, I decline to talk toor with either of my unwelcome visitors. If you have to conduct thisofficial inquisition, go on with it, but I refuse to speak except toanswer your questions. Eliza, you are not to talk, either."

"Good!" said Gibbs, "just what I want." And he spoke sincerely, for hebegan to see that he would learn little from the display of rancor andtemper that moved them all.

He put definite and straightforward questions, and elicited theinformation that they were all in their beds and asleep at the hour ofthe murder. This could not be corroborated from the very nature ofthings, but he let it pass.

There was fierce disagreement as to which had first declared awillingness to kill Sir Herbert Binney, and which had said she, too, wasinclined to the deed, but it was admitted that such hasty andunconsidered declarations had been made.

In fact, the gist of the long and difficult grilling was an apparentdetermination on the part of each one of the two factions to accuse theother, and a most plausible and complacent assumption of innocence byboth.

This seemed a non-committal situation, but Gibbs did not deem it such.He was definitely persuaded as to the guilty party, and his satisfiednods and approving smiles showed Richard Bates plainly which way thedetective's opinions leaned.

And the young man was thoroughly frightened. Though, for his part, itwould be a difficult matter to make a preference between the belief inthe guilt of his aunt or the guilt of the mother of the girl he loved.

And the trend of Gibbs' investigation led surely to one or the other.The use of the paper-cutter that Miss Prall admitted having given intoSir Herbert's keeping gave wide-spread opportunity. Any one desiring tokill the man had a means provided, that is, reasoning that Sir Herberthad the knife with him for the purpose of getting it mended.

Again, that story might be pure fabrication, in which case the suspicionswung back to Miss Prall and Eliza.

It was Gibbs' theory that the unintelligible letters of the dead man'smessage implied two women and the attempted direction was to get both.This, he argued, meant either Miss Prall and Eliza Grundy or Mrs Everettand her faithful aide, Kate Holland.

It seemed to him that the case narrowed itself down to these women,either pair of which had both motive and opportunity.

The affair between Bates and Dorcas was, of course, known to bothguardians, though they tried to disbelieve it, and probably didn't knowto what lengths it had already gone. But Mrs Everett knew that SirHerbert approved the match and doubtless feared that her modern andup-to-date daughter might take the reins in her own hands. Therefore herdesire to have Sir Herbert removed was explainable. She felt sure thatwithout his Uncle's insistence on Richard's entering the Bun business,the young man would return to his inventions and so forget Dorcas in hiswork. At least, that's the nearest Gibbs could come to her motive,though he felt sure there was more to be learned regarding that. MrsEverett was deep and very plausible of manner. She had, he knew,underlying motives and hidden capabilities that would lead her, with theassistance of the Amazonian Kate, anywhere.

On the other hand, Miss Prall wanted the old man out of the say, so thather nephew would lack his advice and assistance concerning the affairwith Dorcas, and the aunt felt that, with Sir Herbert out of it, shecould easily persuade Richard to return to the great work in which hewas so deeply interested and forget the girl. Moreover, she knew thatMrs Everett, no more desiring the marriage of the young people than shedid herself, was planning to move away, and then all would be well.

The motives were not altogether clear, but, Gibbs reasoned, there mustbe many points that were hidden and would remain so, with these cleverwomen to guard them.

He tactfully tried to draw them out, but with even greater tact theyevaded and eluded his questions and contradicted each other andoccasionally,--and purposely,--themselves, until the detective began tothink the determined masculine mind is no match for the equallydetermined Eternal Feminine.

Indeed, involuntarily and almost unconsciously, they joined forcesagainst him, and presently found themselves aiding each other, which,when they realized it, made them more angry,--if possible,--than before.

At last Mrs Everett looked at her watch.

"I've an appointment that I'm anxious to keep," she said, drawlingly;"as you don't seem to be getting anywhere, Mr Detective, can you not letme go, and finish up this absorbing discussion with Miss Prall?"

"You're quite mistaken in assuming that I'm not getting anywhere, MrsEverett," returned the nettled detective, "but you may go if you wish.In fact, I allow it, because I have learned about all there is tolearn,--not so insignificant an amount as you imply."

Mrs Everett looked at him sharply and was momentarily disconcertedenough to gasp out:

"Oh, have you a clue?"

"Several," Gibbs returned, carelessly. "Nothing that I care to makeknown, but I've found out enough to set me on the right track."

Covertly he watched the faces to see how this struck the two principals.

With little result, for Mrs Everett, regaining her poise, merely smiledin an exasperating way, and Miss Prall looked coldly disinterested.

"Wonderful characters," Gibbs commented to himself, for he had neverbefore met women who could so perfectly hide their feelings.

And he was sure that one of them, at least, was hiding her emotion; thatone of them was really aghast at the thought of exposure and was tryingwith all her powers to conceal her dismay.

The maid, Kate, and the companion, Eliza, merely mirrored the other'scalm. Eliza, glancing at Miss Prall, took her cue and looked disdainfulof the whole affair. Kate Holland curled a scornful lip and nodded herhead in Miss Prall's direction.

And yet, if one pair were guilty the other two were innocent. Collusionbetween the two factions was unthinkable. But Gibbs had made up hismind, and he rose and opened the door.

"If you must keep your appointment, Madame, you are excused. I may saythat you are under surveillance, but I have little fear of your tryingto get away secretly, and unless you do, you will not be bothered in anyway."

"Your surveillance does not interest me," and, with a sublime disregardof all present, Mrs Everett swept out of the room, followed by the largeand somewhat ungainly Kate.

"I don't want to discuss this thing," Gibbs began, as he himselfprepared to leave,--"but----"

"I don't want to discuss it either," said Bates, and his tone was fullof indignation. "There is no room for discussion after this asinineperformance of yours! You're not fit to be a detective! You get someladies together and badger them into all sorts of thoughtless, unmeantadmissions and call that testimony! I'm surprised at you, Gibbs. And Itell you frankly what I mean to do. I'm going out,--right now,--to get adetective who can detect! A man who knows the first principles of thebusiness,--which you don't even seem to dream of! I've had enough ofyour futile questioning, your unfounded suspicions, your absurddeductions! I'm off!"

The Deep Lake Mystery

The Deep Lake Mystery The Man Who Fell Through the Earth

The Man Who Fell Through the Earth The Mystery of the Sycamore

The Mystery of the Sycamore The Mystery Girl

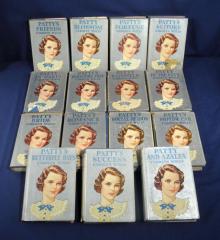

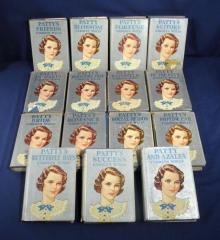

The Mystery Girl Patty Blossom

Patty Blossom Patty and Azalea

Patty and Azalea The Room with the Tassels

The Room with the Tassels The Vanishing of Betty Varian

The Vanishing of Betty Varian Murder in the Bookshop

Murder in the Bookshop The Staying Guest

The Staying Guest The Curved Blades

The Curved Blades Patty—Bride

Patty—Bride The Mark of Cain

The Mark of Cain Two Little Women on a Holiday

Two Little Women on a Holiday Marjorie's New Friend

Marjorie's New Friend Patty's Fortune

Patty's Fortune Patty's Social Season

Patty's Social Season Patty in Paris

Patty in Paris The Diamond Pin

The Diamond Pin The Come Back

The Come Back The Dorrance Domain

The Dorrance Domain Marjorie at Seacote

Marjorie at Seacote Patty's Butterfly Days

Patty's Butterfly Days Patty's Motor Car

Patty's Motor Car Patty's Success

Patty's Success Patty's Suitors

Patty's Suitors Patty's Summer Days

Patty's Summer Days Two Little Women

Two Little Women Patty Fairfield

Patty Fairfield Marjorie's Busy Days

Marjorie's Busy Days Betty's Happy Year

Betty's Happy Year In the Onyx Lobby

In the Onyx Lobby Marjorie's Maytime

Marjorie's Maytime The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK®

The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK® The Gold Bag

The Gold Bag The Clue

The Clue The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery

The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery