- Home

- Carolyn Wells

The Luminous Face

The Luminous Face Read online

Produced by Roger Frank and Sue Clark

THE LUMINOUS FACE

by

CAROLYN WELLS

Author of

"The Come Back," "In the Onyx Lobby," "The Curved Blades" etc.

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers :: New York

Published by arrangement with George H. Doran Company

COPYRIGHT, 1921,

BY GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I--Doctor Fell CHAPTER II--The Telephone Call CHAPTER III--The Lindsays CHAPTER IV--Pollard's Threat CHAPTER V--Mrs Mansfield's Story CHAPTER VI--The Fur Collar CHAPTER VII--Barry's Suspect CHAPTER VIII--Miss Adams' Story CHAPTER IX--Ivy Hayes CHAPTER X--The Signed Letter CHAPTER XI--Miss Adams Again CHAPTER XII--Louis' Confession CHAPTER XIII--Philip and Phyllis CHAPTER XIV--Hester's Statement CHAPTER XV--Phyllis and Ivy CHAPTER XVI--Buddy CHAPTER XVII--Zizi CHAPTER XVIII--The Luminous Face

THE LUMINOUS FACE

CHAPTER I

DOCTOR FELL

"A bit thick, I call it," Pollard looked round the group; "here'sMellen been dead six weeks now, and the mystery of his taking-offstill unsolved."

"And always will be," Doctor Davenport nodded. "Mighty few murders arebrought home to the villains who commit them."

"Oh, I don't know," drawled Phil Barry, an artist, whose dress anddemeanor coincided with the popular idea of his class. "I've no headfor statistics," he went on, idly drawing caricatures on the margin ofhis evening paper as he talked, "but I think they say that onlyone-tenth of one per cent, of the murderers in this great and gloriouscountry of ours are ever discovered."

"Your head for statistics is defective, as you admit," DoctorDavenport said, his tone scornful; "but percentages mean little inthese matters. The greater part of the murders committed are notbrought prominently before public notice. It's only when the victim isrich or influential, or the circumstances of some especial interestthat a murder occupies the front pages of the newspapers."

"Old Mellen's been on those same front pages for several weeks--offand on, that is," Pollard insisted; "of course, he was a well-knownman and his exit was dramatic. But all the same, they ought to havecaught his murderer--or slayer, as the papers call him."

"Him?" asked Barry, remembering the details of the case.

"Impersonal pronoun," Pollard returned, "and probably a man anyway.'Cherchez la femme,' is the trite advice, and always sounds well, butreally, a woman seldom has nerve enough for the fatal deed."

"That's right," Davenport agreed. "I know lots of women who have allthe intent of murder in their hearts, but who never could pull itoff."

"A good thing, too," Barry observed. "I'd hate to think any woman Iknow capable of murder! Ugh!" His long, delicate white hand waved awaythe distasteful idea with a gesture that seemed to dismiss itentirely.

There were not many in the Club lounge, the group of men had it mostlyto themselves, and as the afternoon dusk grew deeper and the lightswere turned on, several more went away, and finally Fred Lane rose togo.

"Frightfully interesting, you fellows," he said, "but it's after five,and I've a date. Anybody I can drop anywhere?"

"Me, please," accepted Dean Monroe. "That is, if you're going my way.I want to go downtown."

"Was going up," returned Lane, "but delighted to change my route. Comealong, Monroe."

But Monroe had heard a chance word from Doctor Davenport that arrestedhis attention, and he sat still.

"Guess I won't go quite yet--thanks all the same," he nodded at Lane,and lighted a fresh cigarette.

Dean Monroe was a younger man than the others, an artist, but not yetin the class with Barry. His square, firm-set jaw, and his Wedgwoodblue eyes gave his face a look of power and determination quite incontrast with Philip Barry's pale, sensitive countenance. Yet the twowere friends--chums, almost, and though differing in their views onart, each respected the other's opinions.

"Have it your own way," Lane returned, indifferently, and went off.

"Crime detection is not the simple process many suppose," Davenportwas saying, and Monroe gave his whole attention. "So much depends onchance."

"Now, Doctor," Monroe objected, "I hold it's one of the most exactsciences, and----"

Davenport looked at him, as an old dog might look at an impertinentkitten.

"Being an exact science doesn't interfere with dependence on chance,"he growled; "also, young man, are you sure you know what an exactscience is?"

"Yeppy," Monroe defended himself, as the others smiled a little."It's--why, it's a science that's exact--isn't it?"

His gay smile disarmed his opponent, and Davenport, mounted on hishobby, went on: "You may have skill, intuition, deductive powers andall that, but to discover a criminal, the prime element is chance.Now, in the Mellen case, the chances were all against the detectivesfrom the first. They didn't get there till the evidences were, ormight have been destroyed. They couldn't find Mrs Gresham, the mostimportant witness until after she had had time to prepare her stringof falsehoods. Oh, well, you know how the case was messed up, and now,there's not a chance in a hundred of the truth ever being known."

"Does chance play any part in your profession, Doctor?" asked Monroe,with the expectation of flooring him.

"You bet it does!" was the reply. "Why, be I never so careful in mydiagnosis or treatment, a chance deviation from my orders on the partof patient or attendant, a chance draught of wind, or upsetnerves--oh, Lord, yes! as the Good Book says, 'Time and Chancehappeneth to us all.' And no line of work is more precarious thanestablishing a theory or running down a clew in a murder case. For thecriminal, ever on the alert, has all the odds on his side, and canblock or divert the detective's course at will."

Doctor Ely Davenport was, without being pompous, a man who was at alltimes conscious of his own personality and sure of his own importance.He was important, too, being one of the most highly thought of doctorsin New York City, and his self-esteem, if a trifle annoying, wasfounded on his real worth.

He often said that his profession brought him in contact with thesouls of men and women quite as much as with their bodies, and he wasfond of theorizing what human nature might do or not do in crucialmoments.

The detection of crime he held to be a matter requiring the highestintelligence and rarest skill.

"Detection!" he exclaimed, in the course of the present conversation,"why detection is as hard to work out as the Fourth Dimension! Asdifficult to understand as the Einstein theory."

"Oh, come now, Doctor," Pollard said, smiling, "that's going a bit toofar. I admit, though, it requires a superior brain. But any real workdoes. However, I say, first catch your motive."

"That's it," broke in Monroe, eagerly. "It all depends on the motive!"

"The crime does," Davenport assented, drily, "but not the detection.You youngsters don't know what you're talking about--you'd better shutup."

"We know a lot," returned Monroe, unabashed. "Youth is no barrier toknowledge these days. And I hold that the clever detective seeks firstthe motive. You can't have a murder without a motive, any more than anomelette without eggs."

"True, oh, Solomon," granted the doctor. "But the motive may be knownonly to the murderer, and not to be discovered by any effort of theinvestigator."

"Then the murder mystery remains unsolved," returned Monroe, promptly.

"Your saying so doesn't make it so, you know," drawled Phil Barry, inhis impertinent way. "Now, to me it would seem that a nice lot ofcircumstantial evidence, and a few good clews would expedite mattersjust as well as a knowledge of the villain's motive."

"Circumstantial evidence!" scoffed Monroe.

"Sure," rejoined B

arry; "Give me a smoking revolver with initials onit, a dropped handkerchief, monogrammed, of course, half a brokencuff-link, and a few fingerprints, and I care not who knows themotive. And if you can add a piece--no, a fragment of tweed, clutchedin the victim's rigid hand--why--I'll not ask for wine!"

"What rubbish you all talk," said Pollard, smiling superciliously;"don't you see these things all count? If you have motive you don'tneed evidence, and _vice versa_. That is, if both motive andevidence are the real thing."

"There are only three motives," Monroe informed. "Love, hate andmoney."

"You've got all the jargon by heart, little one," and Pollard grinnedat him. "Been reading some new Detective Fiction?"

"I'm always doing that," Monroe stated, "but I hold that a detectivewho can't tell which of those three is the motive, isn't worth hissalt."

"Salt is one commodity that has remained fairly inexpensive," saidBarry, speaking slowly, and with his eyes on his cigarette, from whichhe was carefully amputating the ash, "and a detective who could trulydiagnose motive is not to be sneezed at. Besides, revenge is often areason."

"That comes under the head of hate," promptly responded Monroe. "Thethree motives include all the gamut of human emotion, and some oftheir ramifications will include every murder motive that everexisted."

"Fear?" quietly suggested Doctor Davenport.

"Part of hate," said Monroe, but he was challenged by Pollard.

"Not necessarily. A man may fear a person whom he does not hate atall. But there's another motive, that doesn't quite fit yourclassification, Monroe."

Before the inevitable question could be put another man joined thegroup.

"Hello, folks," said Robert Gleason, as he sat down; "hope I don'tintrude--and all that. What you talking about?"

"Murder," said Barry. "Murder as a Fine Art, you know."

"Don't like the subject. Let's change it. Talk about the ladies, orsomething pleasant, you know. Eh?"

"Or Shakespeare and the musical glasses," said Pollard.

"No musical glasses, nowadays," bewailed Gleason. "No more clink thecanakin, clink. It's drink to me only with thine eyes. Hence, thepreponderance of women and song in our lives, since the third of thetrio is gone."

Gleason was the sort of Westerner usually described as breezy. He wason intimate terms with everybody, whether everybody reciprocated ornot. Not a large man, not a young man, he possessed a restlessvitality, a wiry energy that gave him an effect of youth. About forty,he was nearer the age of Doctor Davenport than the others, who wereall in their earliest thirties.

Nobody liked Gleason much, yet no one really disliked him. He was abit forward, a little intrusive, but it was clear to be seen thatthose mannerisms were due to ignorance and not to any intent to beobjectionable. He was put up at the Club by a friend, and had neverreally overstepped his privileges, though it was observable that hisways were not club ways.

"Yep, the Ladies--God bless 'em!" he went on. "What could be a bettersubject for gentlemen's discussion? No personalities, of course; thatgoes without saying."

"Then why say it?" murmured Pollard, without looking at the speaker.

"That's so! Why, indeed?" was the genial response. "Now, you know, outin Seattle, where I hail from, there's more--oh, what do you call it,sociability like, among men. I go into a club there and everybodysings out something gay; I come in here, and you all shut up likeclams."

"You objected to the subject we were discussing," began Monroe,indignantly, but Barry interrupted, with a wave of his hand, "Theeffete East, my dear Gleason. Doubtless you've heard that expression?Yes, you would. Well, it's our renowned effeteness that prevents ourfalling on your neck more effusively."

"Guying me?" asked Gleason, with a quiet smile. "You see, boys, beforeI went to Seattle, I was born in New England. I can take a littlechaff."

"You're going to tell us of your ancestry?" said Pollard, and thoughhis words were polite his tone held a trace of sarcastic intent.

Gleason turned a sudden look on him.

"I might, if you really want me to," he said, slowly. "I might giveyou the story of my life from my infancy, spent in Coggs' Hollow, NewHampshire, to the present day, when I may call myself one of theleading citizens of Seattle, Wash."

"What or whom do you lead?" asked Pollard, and again the only trace ofunpleasantness was a slight inflection in his really fine voice.

"I lead the procession," and Gleason smiled, as one who positivelyrefuses to take offense whether meant or not. "But, I can tell you Idon't lead it here in New York! Your pace is rather swift for me! I'mhaving a good time and all that, but soon, it's me for the wildnessand woolliness of the good old West again! Why, looky here, I'm livingin a hole in the wall--yes, sir, a hole in the wall!"

"I like that!" laughed Doctor Davenport. "Why, man, you're in thatapartment of McIlvaine's--one of the best put-ups in town."

"Yes, so Mac said," Gleason exploded. "Why, out home, we'd call that acoop. But what could I do? This old town of yours, spilling over full,couldn't fix me out at any hotel, so when my friend offered hispalatial home, I took it--and----"

"You'd be surprised at the result!" Barry broke in. "That's becauseyou're a Western millionaire, Mr Gleason. Now we poor, strugglingyoung artists think that apartment you're in, one of the finestdiggings around Washington Square."

"But, man, there's no service!" Gleason went on, complainingly. "Noteven a hall porter! Nobody to announce a caller!"

"Well, you have that more efficient service, the----"

"Yes! the contraption that lets a caller push a button and have thedoor open in his face!"

"Isn't that just what he wants?" said Barry, laughing outright atGleason's disgusted look. "Then, you see, Friend Caller walksupstairs, and there you are!"

"Yes, _walks_ upstairs. Not even an elevator!"

"But your friends don't need one," expostulated Davenport. "You'reonly one flight up. You don't seem to realize how lucky you are to getthat place, in these days of housing problems!"

"Oh, well, 'tis not so deep as a well, nor so wide as a church door,but it will serve," said Gleason, with one of his sudden, pleasantsmiles.

"I see your point, though, Mr Gleason," said Dean Monroe. "And if Iwere a plutocrat from Seattle, sojourning in this busy mart, I confessI, too, should like a little more of the dazzling light in my hallsthan you get down there. I know the place, used to go there to seeMcIlvaine. And while it's a decent size, and jolly well furnished, Ican see how you'd prefer more gilt on your ginger bread."

"I do, and I'd have it, too, if I were staying here much longer. ButI'm going to settle up things soon now, and go back to home, sweethome."

"How did you, a New Englander, chance to make Seattle your home?"asked Monroe, always of a curious bent.

"Had a chance to go out there and get rich. You see, Coggs' Hollow, asone might gather from its name, was a small hamlet. I lived there tillI was twenty-five, then, getting a chance to go West and blow up withthe country, I did. Glad of it, too. Now, I'm going back there, and--Ihope to take with me a specimen of your fair feminine. Yes, sir, Ihope and expect to take along, under my wing, one of these littlemoppy-haired, brief-skirted lassies, that will grace my Seattle homesomething fine!"

"Does she know it yet?" drawled Barry and Gleason stared at him.

"She isn't quite sure of it, but I am!" he returned with a comical airof determination.

"You know her pretty well, then," chaffed Barry.

"You bet I do! I ought to. She's my sister's stepdaughter."

"Phyllis Lindsay!" cried Barry, involuntarily speaking the name.

"The same," said Gleason, smiling; "and as I'm due there for dinner,I'll be toddling now to make myself fine for the event."

With a general beaming smile of good nature that included all thegroup, Gleason went away.

For a few moments no one spoke, and then Monroe began, "As I wassaying, there are only three motives for murder--and I stick to that.But you were about to say, Pollard

----?"

"I was about to say that you have omitted the most frequent and mostimpelling motive. It doesn't always result in the fatal stroke, but asa motive, it can't be beat."

"Go on--what is it?"

"Just plain dislike."

"Oh, hate," said Monroe.

"Not at all. Hate implies a reason, a grievance. But I mean anineradicable, and unreasonable dislike--why, simply a case of:

'I do not like you, Doctor Fell, The reason why I cannot tell; But this I know and know full well, I do not like you, Doctor Fell.'

One Tom Brown wrote that, and it's a bit of truth, all right!"

"One Martial said it before your friend Brown," informed DoctorDavenport. "He wrote:

'Non amo, te, Sabidi, nec possum dicere quore; Hoc tantum possum dicere, non amo te.'

Which is, being translated for the benefit of you unlettered ones, 'Ido not love thee, Sabidius, nor can I say why; this only can I say, Ido not love thee.' There's a French version, also."

"Never mind, Doc," Pollard interrupted, "we don't want your erudition,but your opinion. You say you know psychology as well as physiology;will you agree that a strong motive for murder might be just thatunreasonable dislike--that distaste of seeing a certain personaround?"

"No, not a strong motive," said Davenport, after a short pause forthought. "A slight motive, perhaps, by which I mean a fleetingimpulse."

"No," persisted Pollard, "an impelling--a compelling motive. Why,there's Gleason now. I can't bear that man. Yet I scarcely know him.I've met him but a few times--had little or no personal conversationwith him--yet I dislike him. Not detest or hate or despise--merelydislike him. And, some day I'm going to kill him."

"Going to kill all the folks you dislike?" asked Barry, indifferently.

"Maybe. If I dislike them enough. But that Gleason offends my taste. Ican't stand him about. So, as I say, I'm going to kill him. And I holdthat the impulse that drives me to the deed is the strongest murdermotive a man can have."

"Don't talk rubbish, Manning," and young Monroe gave him a frightenedglance, as if he thought Pollard in earnest.

"It isn't altogether rubbish," said Doctor Davenport, as he rose togo, "there's a grain of truth in Pollard's contention. A rooteddislike of another is a bad thing to have in your system. Have it cutout, Pollard."

"You didn't mean it, did you, Manning?"

Monroe spoke diffidently, almost shyly, with a scared glance atPollard.

The latter turned and looked at him with a smile. Then, glaringferociously, he growled, "Of course I did! And if you get yourselfdisliked, I'll kill you, too! _Booh!_"

They all laughed at Monroe's frightened jump, as Pollard Booh'd intohis face, and Doctor Davenport said, "Look out, Pollard, don't scareour young friend into fits! And, remember, Monroe, 'Threatened men livelong?' I've my car--anybody want a lift anywhere?"

"Take me, will you?" said Dean Monroe, and willingly enough, DoctorDavenport carried the younger man off in his car.

"You oughtn't to do it, Pol, you know," Barry gently remonstrated."Poor little Monroe thinks you're a gory villain, and he'll mull overyour fool remarks till he's crazy--more crazy than he is already."

"Let him," said Pollard, smiling indifferently. "I only spoke thetruth--as to that motive, I mean. Don't you want to kill that Gleasonevery time you see him?"

"You make him seem like a cat--with nine or more lives! How _can_you kill a man every time you see him? It isn't done!"

The two men left the Club together, and walked briskly down FifthAvenue.

"Going to the Lindsays' to-night, of course?" asked Barry, as theyreached Forty-fifth Street, where he turned off.

"Yes. You?"

"Yes. See you later, then. You gather that Gleason has annexed thepretty Phyllis?"

"Looks like it, doesn't it? I suppose the announcement will be madeto-night at the dinner or the dance."

"Suppose so. How I hate to see it that way. I'm in love with thatlittle beauty myself."

"Who isn't?" returned Pollard, smiling, and then Barry turned off inhis own street, and Pollard went on down toward his home, a smallhotel on West Fortieth.

Held up for a few moments by the great tide of traffic at Forty-secondStreet, he glanced at his wrist watch and found it was ten minutesafter six. And then, a taxicab passed him, and in it he saw PhyllisLindsay. She did not see him, however, so, the traffic signal beinggiven, he went on his way.

The Deep Lake Mystery

The Deep Lake Mystery The Man Who Fell Through the Earth

The Man Who Fell Through the Earth The Mystery of the Sycamore

The Mystery of the Sycamore The Mystery Girl

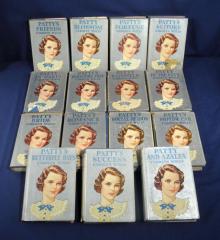

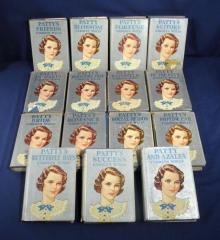

The Mystery Girl Patty Blossom

Patty Blossom Patty and Azalea

Patty and Azalea The Room with the Tassels

The Room with the Tassels The Vanishing of Betty Varian

The Vanishing of Betty Varian Murder in the Bookshop

Murder in the Bookshop The Staying Guest

The Staying Guest The Curved Blades

The Curved Blades Patty—Bride

Patty—Bride The Mark of Cain

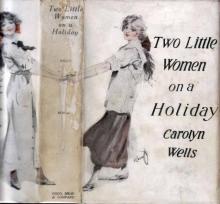

The Mark of Cain Two Little Women on a Holiday

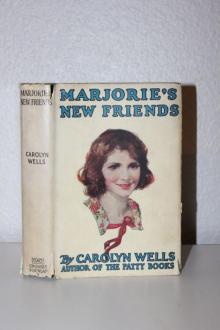

Two Little Women on a Holiday Marjorie's New Friend

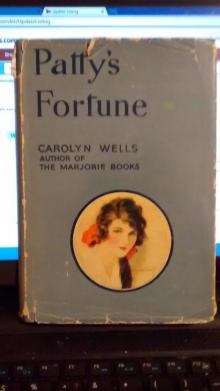

Marjorie's New Friend Patty's Fortune

Patty's Fortune Patty's Social Season

Patty's Social Season Patty in Paris

Patty in Paris The Diamond Pin

The Diamond Pin The Come Back

The Come Back The Dorrance Domain

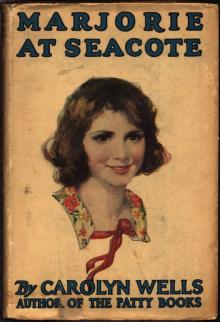

The Dorrance Domain Marjorie at Seacote

Marjorie at Seacote Patty's Butterfly Days

Patty's Butterfly Days Patty's Motor Car

Patty's Motor Car Patty's Success

Patty's Success Patty's Suitors

Patty's Suitors Patty's Summer Days

Patty's Summer Days Two Little Women

Two Little Women Patty Fairfield

Patty Fairfield Marjorie's Busy Days

Marjorie's Busy Days Betty's Happy Year

Betty's Happy Year In the Onyx Lobby

In the Onyx Lobby Marjorie's Maytime

Marjorie's Maytime The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK®

The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK® The Gold Bag

The Gold Bag The Clue

The Clue The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery

The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery