- Home

- Carolyn Wells

The Clue Page 13

The Clue Read online

Page 13

“Miss Dupuy’s behavior has certainly invited criticism,” began Rob, but before he could go further, the French girl, Marie, appeared at the door, and seemed about to enter.

“What is it, Marie?” said Kitty kindly. “Are you looking for me?”

“Yes, mademoiselle,” said Marie, “and I would speak with monsieur too. I have that to say which is imperative. Too long already have I kept the silence. I must speak at last. Have I permission?”

“Certainly,” said Fessenden, who saw that Marie was agitated, but very much in earnest. “Tell us what you have to say. Do not be afraid.”

“I am afraid,” said Marie, “but I am afraid of one only. It is the Miss Morton, the stranger lady.”

“Miss Morton?” said Kitty, in surprise. “She won’t hurt you; she has been very good to you,”

“Ah, yes, mademoiselle; but too good. Miss Morton has been too kind, too sweet, to Marie! It is that which troubles me.”

“Well, out with it, Marie,” said Rob. “Close that door, if you like, and then speak out, without any more beating around the bush.”

“No, monsieur, I will no longer beat the bush; I will now tell.”

Marie carefully closed the door, and then began her story:

“It was the night of the—of the horror. You remember, Miss French, we sat all in this very room, awaiting the coming of the great doctor—the doctor Leonard.”

“Yes,” said Kitty, looking intently at the girl; “yes, I know most of you stayed here waiting,—but I was not here; Doctor Hills sent Miss Gardner and me to our rooms.”

“Yes; it is so. Well, we sat here, and Miss Morton rose with suddenness and left the room. I followed, partly that I thought she might need my services, and partly—I confess it—because I trusted her not at all, and I wished to assure myself that all was well. I followed her,—but secretly,—and I—shall I tell you what she did?”

Kitty hesitated. She was not sure she should listen to what was, after all, servants’ gossip about a guest of the house.

But Fessenden looked at it differently. He knew Marie had been the trusted personal maid of Miss Van Norman, and he deemed it right to hear the evidence that she was now anxious to give.

“Go on, Marie,” he said gravely. Be careful to tell it exactly as it happened, whatever it is.”

“Yes, m’sieur. Well, then, I softly followed Miss Morton, because she did not go directly to her own room, but went to Miss Van Norman’s sitting-room and stood before the desk of Miss Madeleine.”

“You are sure, Marie?” said Kitty, who couldn’t help feeling it was dishonorable to listen to this.

“Please, Miss French, let her tell the story in her own way,” said Rob. “It is perhaps of the utmost importance, and may lead to great results.”

Then Marie went uninterruptedly on.

“She stood in front of the desk, m’sieur; she searched eagerly for papers, reading and discarding several. Then she found some, which she saw with satisfaction, and hastily concealed in her pocket. Miss Morton is a lady who yet has pockets in her gowns. With the papers in her pocket, then, Miss Morton looks about carefully, and, thinking herself unobserved, creeps, but stealthily, to her own room. There—m’sieur, I was obliged to peep at the keyhole—there she lighted a fire in her grate, and burned those papers. With my eyes I saw her. Never would I have told, for it was not my affair, but that I fear for Miss Dupuy. It is in the air that she knows secrets concerning Miss Van Norman’s death. Ah, if one would know secrets, one should question Miss Morton.”

“This is a grave charge you bring against the lady, Marie,” said Fessenden.

“Yes, monsieur, but it is true.”

“I know it is true,” said Kitty; “I have not mentioned it before, but I saw Miss Morton go to Madeleine’s room that night, and afterward go to her own room. I knew nothing, of course, of the papers, and so thought little of the whole incident, but if she really took papers from Madeleine’s desk and burned them, it’s indeed important. What could the papers have been?”

“You know she inherited,” began Fessenden.

“Oh, a will!” cried Kitty.

“Marie, you may go now,” Rob interrupted; “you did right to tell us this, and rest assured you shall never be blamed for doing so. You will probably be questioned further, but for the present you may go. And thank you.”

Marie curtseyed and went away.

“She’s a good girl,” said Kitty. “I always liked her; and she must have heard, as I did, so much of Cicely’s chatter, that she feared some sort of suspicion would fall on Cicely, and she wanted to divert it toward Miss Morton instead.”

“As usual, with your quick wits, you’ve gone right to the heart of her motive,” said Rob; “but it may be more serious than you’ve yet thought of. Miss Morton inherits, you know.”

“Yes, now,” said Kitty significantly, “since she burnt that other will.”

“What other will?”

“Oh, don’t you see? The will she burnt was a later one, that didn’t give her this house. She burnt it so the earlier one would stand.”

“How do you know this?”

“I don’t know it, except by common sense! What else would she take from Maddy’s desk and burn except a will? And, of course, a will not in her favor, leaving the one that did bequeath the house to her to appear as the latest will.”

“Does this line of argument take us any further?” said Rob, so seriously that Kitty began to think.

“You don’t mean,” she whispered, “that Miss Morton—in order to—”

“To receive her legacy.”

“Could—no, she couldn’t! I won’t even think of it!”

“But you thought of Miss Dupuy. Miss French, as I told you yesterday, we must think of every possible person, not every probable one. These suggestions are not suspicions—and they harm no one who is innocent.”

“I suppose that is so. Well, let us consider Miss Morton then, but of course she didn’t really kill Maddy.”

“I trust not. But I must say I could sooner believe it of a woman of her type than Miss Dupuy’s.”

“But Cicely didn’t either! Oh, how can you say such dreadful things!”

“We won’t say them any more. They are dreadful. But I thought you were going to help me in my detective work, and you balk at every turn.”

“No, I won’t,” said Kitty, looking repentant. “I do want to help you; and if you’ll let me help, I’ll suspect everybody you want me to.”

“I want you to help me, but this story of Marie’s is too big for me to handle by myself. I must put that into Mr. Benson’s hands. It is really more important than you can understand.”

“I suppose so,” said Kitty, so humbly that Rob smiled at her, and had great difficulty to refrain from kissing her.

XVI

SEARCHING FOR CLUES

BELIEVING THAT MARIE’S INFORMATION about Miss Morton was of deep interest, Rob started off at once to confer with Coroner Benson about it.

As he walked along he discussed the affair with himself, and was shocked to realize that for the third time he was suspecting a woman of the murder.

“But how can I help it?” he thought impatiently. “The house was full of women, and not a man in it except the servants, and no breath of suspicion has blown their way. And if a woman did do it, that unpleasant Morton woman is by far the most likely suspect. And if she was actuated by a desire to get her inheritance, why, there’s the motive, and she surely had opportunity. It’s a tangle, but we must find something soon to guide us. A murder like that can’t have been done without leaving some trace somewhere of the criminal.” And then Fessenden’s thoughts drifted away to Kitty French, and he was quite willing to turn the responsibility of his new information over to Mr. Benson. On his way to the coroner’s office he passed the Mapleton Inn. An impulse c

ame to him to investigate Tom Willard’s statements, and he turned back and entered the small hotel.

He thought it wiser to be frank in the matter than to attempt to obtain underhand information. Asking to speak with the proprietor alone, he said plainly:

“I’m a detective from New York City, and my name is Fessenden. I’m interested in investigating the death of Miss Van Norman. I have no suspicions of any one in particular, but I’m trying to collect a few absolute facts by way of making a beginning. I wish you, therefore, to consider this conversation confidential.”

Mr. Taylor, the landlord of the inn, was flattered at being a party to a confidential conversation with a real detective, and willingly promised secrecy in the matter.

“Then,” went on Fessenden, “will you tell me all you know of the movements of Mr. Willard last evening?”

Mr. Taylor looked a bit disappointed at this request, for he foresaw that his story would be but brief. However, he elaborated the recital and spun it out as long as he possibly could. But after all his circumlocution, Fessenden found that the facts were given precisely as Willard had stated them himself.

The bellboy who had carried up the suitcase was called in, and his story also agreed.

“Yessir,” said the boy; “I took up his bag, and he gimme a quarter, just like any nice gent would. ‘N’en I come downstairs, and after while the gent’s bell rang, and I went up, and he wanted ice water. He was in his shirt sleeves then, jes’ gittin’ ready for bed. So I took up the water, and he said, ‘Thank you,’ real pleasant-like, and gimme a dime. He’s a awful nice man, he is. He had his shoes off that time, ’most ready for bed. And that’s all I know about it.”

All this was nothing more nor less than Fessenden had expected. He had asked the questions merely for the satisfaction of having verbal corroboration of Tom’s own story.

With thanks to Mr. Taylor, and a more material token of appreciation to the boy, he went away.

On reaching the coroner’s office, he was told that Mr. Benson was not in. Fessenden was sorry, for he wanted to discuss the Morton episode with him.

He thought of going to Lawyer Peabody’s, who would know all about Miss Van Norman’s will, but as he sauntered through one of the few streets the village possessed, he was rather pleased than otherwise to see Kitty French walking toward him.

She greeted him with apparent satisfaction, and said chummily, “Let’s walk along together and talk it over.”

Immediately coroner and lawyer faded from Rob’s mind, he willingly fell into step beside her, and they walked along the street which soon merged itself into a pleasant country road.

Fessenden told Kitty of his conversation at the inn, but she agreed that it was unimportant.

“Of course,” she said, “I suppose it was a good thing to have some one else say the same as Tom said, but as Tom wasn’t even in the house, I don’t see as he is in the mystery at all. But there’s no use of looking further for the criminal. It was Schuyler Carleton, just as sure as I stand here.”

Kitty very surely stood there. They had paused beneath an old willow tree by the side of the road, and Kitty, leaning against a rail fence, looked like a very sweet and winsome Portia, determined to mete out justice.

Though he was himself convinced that he was an unprejudiced seeker after truth, at that moment Robert Fessenden found himself very much swayed by the opinions of the pretty, impetuous girl who addressed him.

“I believe I’m going to work all wrong,” he declared. “I can’t help feeling sure that Carleton didn’t do it, and so I’m trying to discover who did.”

“Well, why is that wrong?” demanded Kitty wonderingly.

“Why, I think a better way to do would be to assume, if only for sake of argument, as they say, or rather for sake of a starting-point—to assume that you are right and that Carleton is the evildoer, though I swear I don’t believe it.”

Kitty laughed outright. “You’re a nice detective!” she said. “Are you assuming that Schuyler is the villain, merely to be polite to me?”

“I am not, indeed! I feel very politely inclined toward you, I’ll admit, but in this matter I’m very much in earnest. And I believe, by assuming that Carleton is the man, and then looking for proof of it, we may run across clues that will lead us to the real villain.”

Kitty looked at him admiringly, and for Kitty French to look at any young man admiringly was apt to be a bit disturbing to the young man’s peace of mind.

It proved so in this case, and though Fessenden whispered to his own heart that he would attend first to the vindication of his friend Carleton, his own heart whispered back that after that, Miss French must be considered.

“And so,” said Rob, as they turned back homeward, “I’m going to work upon this line. I’m going to look for clues; real, material, tangible clues, such as criminals invariably leave behind them.”

“Do!” cried Kitty. “And I’ll help you. I know we can find something.”

“You see,” went on Fessenden, his enthusiasm kindling from hers, “the actual stage of the tragedy is so restricted. Whatever we find must be in the Van Norman house.”

“Yes, and probably in the library.”

“Or the hall,” he supplemented.

“What kind of a thing do you expect to find?”

“I don’t know, I’m sure. In the Sherlock Holmes stories it’s usually cigar ashes or something like that. Oh, pshaw! I don’t suppose we’ll find anything.”

“I think in detective stories everything is found out by footprints. I never saw anything like the obliging way in which people make footprints for detectives.”

“And how absurd it is!” commented Rob. “I don’t believe footprints are ever made clearly enough to deduce the rest of the man from.”

“Well, you see, in detective stories, there’s always that ‘light snow which had fallen late the night before.’”

“Yes,” said Fessenden, laughing at her cleverness, “and there’s always some minor character who chances to time that snow exactly, and who knows when it began and when it stopped.”

“Yes, and then the principal characters carefully plant their footprints, going and returning—overlapping, you know—and so Mr. Smarty-Cat Detective deduces the whole story.”

“But we’ve no footprints to help us.”

“No, we couldn’t have, in the house.”

“But if it was Schuyler”

“Well, even if,—he couldn’t make footprints without that convenient ‘light snow’ and there isn’t any.”

“And besides, Schuyler didn’t do it.”

“No, I know he didn’t. But you’re going to assume that, you know, in order to detect the real criminal.”

“Yes, I know I said so; but I don’t believe that game will work, after all.”

“I don’t believe you’re much of a detective, any way,” said Kitty, so frankly that Fessenden agreed.

“I don’t believe I am,” he said honestly. “With the time, place, and number of people so limited, it ought to be easy to solve this mystery at once.”

“I think it’s just those very conditions that make it so hard,” said Kitty, sighing.

And so completely under her spell was Fessenden by this time that he emphatically agreed with her.

When they reached the Van Norman house they found it had assumed the hollow, breathless air that invades a house where death is present.

All traces of decoration had been removed from the drawing-room, and it, like the library, had been restored to its usual immaculate order. The scent of flowers, however, was all through the atmosphere, and a feeling of oppression hovered about like a heavy cloud.

Involuntarily Kitty slipped her hand in Rob’s as they entered.

Fessenden, too, felt the gloom of the place, but he had made up his mind to do some practical work, and d

etaining Harris, who had opened the door for them, he said at once, “I want you to open the blinds for a time in all the rooms downstairs. Miss French and I are about to make a search, and, unless necessary, let no one interrupt us.”

“Very good, sir,” said the impassive Harris, who was becoming accustomed to sudden and unexpected orders.

They had chosen their time well for the search, and were not interrupted. Most of the members of the household were in their own rooms; and there happened to be no callers who entered the house.

Molly Gardner had gone away early that morning. She had declared that if she stayed longer she should be downright ill, and, after vainly trying to persuade Kitty to go with her, had returned alone to New York.

Tom Willard and Lawyer Peabody were in Madeleine’s sitting-room, going over the papers in her desk, in a general attempt to learn anything of her affairs that might be important to know. They had desired Miss Dupuy’s presence and assistance, but that young woman refused to go to them, saying she was still too indisposed, and remained, under care of Marie, in her own room.

Fessenden suggested that Kitty should make search in the library while he did the same in the drawing-room; and that afterward they should change places.

Kitty shivered a little as she went into the room that had been the scene of the tragedy, but she was really anxious to assist Fessenden, and also she wanted to do anything, however insignificant, that would help in the least toward avenging poor Maddy’s death.

And yet it was seemingly a hopeless task. Though she carefully and systematically scrutinized walls, rugs and furniture, not a clue could she find.

She was on her hands and knees under a table when Tom Willard came into the room.

“What are you doing?” he said, unable to repress a smile as Kitty, with her curly hair a bit disheveled, came scrambling out.

“Hunting for clues,” she said briefly.

“There are no clues,” said Tom gravely. “It’s the most inexplicable affair all ’round.”

“Then you have no suspicion of any one?”

The Deep Lake Mystery

The Deep Lake Mystery The Man Who Fell Through the Earth

The Man Who Fell Through the Earth The Mystery of the Sycamore

The Mystery of the Sycamore The Mystery Girl

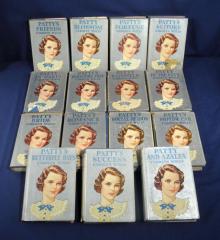

The Mystery Girl Patty Blossom

Patty Blossom Patty and Azalea

Patty and Azalea The Room with the Tassels

The Room with the Tassels The Vanishing of Betty Varian

The Vanishing of Betty Varian Murder in the Bookshop

Murder in the Bookshop The Staying Guest

The Staying Guest The Curved Blades

The Curved Blades Patty—Bride

Patty—Bride The Mark of Cain

The Mark of Cain Two Little Women on a Holiday

Two Little Women on a Holiday Marjorie's New Friend

Marjorie's New Friend Patty's Fortune

Patty's Fortune Patty's Social Season

Patty's Social Season Patty in Paris

Patty in Paris The Diamond Pin

The Diamond Pin The Come Back

The Come Back The Dorrance Domain

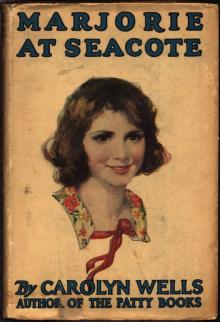

The Dorrance Domain Marjorie at Seacote

Marjorie at Seacote Patty's Butterfly Days

Patty's Butterfly Days Patty's Motor Car

Patty's Motor Car Patty's Success

Patty's Success Patty's Suitors

Patty's Suitors Patty's Summer Days

Patty's Summer Days Two Little Women

Two Little Women Patty Fairfield

Patty Fairfield Marjorie's Busy Days

Marjorie's Busy Days Betty's Happy Year

Betty's Happy Year In the Onyx Lobby

In the Onyx Lobby Marjorie's Maytime

Marjorie's Maytime The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK®

The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK® The Gold Bag

The Gold Bag The Clue

The Clue The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery

The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery