- Home

- Carolyn Wells

The Clue Page 12

The Clue Read online

Page 12

“When an excessively clever young woman assumes an utterly inefficient air,” he thought, “it must be for some undeclared purpose;” and he felt an absurd thrill of satisfaction that though Kitty French was undeniably clever, she put on no ingénue arts to hide it.

Then Kitty’s phrase of “a clinging rosebud” came to his mind, and he realized its exceeding aptness to describe Dorothy Burt. Her appealing eyes and wistful, curved mouth were enough to lure a man who loved her to almost any deed of daring.

“Even murder?” flashed into his brain, and he recoiled at the thought. Old Schuyler might have been made to forget his fealty; he might have been unable to steel his heart against those subtle charms; he might have thrown to the winds his honor and his faith; but surely, never, never, could he have committed that dreadful deed, even for love of this angel-faced siren.

“Could she?”

The words fairly burned into Fessenden’s brain. The sudden thought set his mind whirling. Could she? Why, no, of course not! Absurd! Yes, but could she? What? That child? That baby-girl? Those tiny, rose-leaf hands! Yes, but could she?

“No!” said Fessenden angrily, and then realized that he had spoken aloud, and his hearers were looking at him with indulgent curiosity.

“Forgive me,” he said, smiling as he looked at Mrs. Carleton. “My fancy took a short but distant flight, and I had to speak to it sternly by way of reproof.”

“I didn’t know a lawyer could be fanciful,” said Mrs. Carleton. “I thought that privilege was reserved for poets.”

“Thank you for a pretty compliment to our profession,” said Rob. “We lawyers are too often accused of giving rein to our fancy, when we should be strapped to the saddle of slow but sure Truth.”

“But can you arrive anywhere on such a prosaic steed?” asked Miss Burt, smiling at his words.

“Yes,” said Rob; “we can arrive at facts.”

What prompted him to speak so curtly, he didn’t know; but his speech did not at all please Miss Burt. Her color flew to her cheeks, though she said nothing, and then, as Mrs. Carleton rose from the table, the two ladies smiled and withdrew, leaving Rob alone with his host.

“It’s all right, old boy, of course,” said Carleton, “but did you have any reason for flouting poor little Dorothy like that?”

“No, I didn’t,” said Fessenden honestly and apologetically. “I spoke without thinking, and I’m sorry for it.”

“All right—it’s nothing. Now, Rob, old fellow, you can’t deceive me. I saw a curious expression in your eyes as you looked at Miss Burt tonight, and—well, there is no need of words between us, so I’ll only tell you you’re all wrong there. You look for hidden meanings and veiled allusions in everything that girl says, and there aren’t any. She’s as frank and open-natured as she can be, and—forgive me—but I want you to let her alone.”

Fessenden was astounded. First, at Carleton’s insight in discovering his thoughts, and second, at Carleton’s mistaken judgment of Miss Burt’s nature.

But he only said, “All right, Schuyler; what you say, goes. Would you rather not talk at all about the Van Norman affair?” Fessenden spoke thus casually, for he felt sure it would make it easier for Carleton than if he betrayed a deeper interest.

“Oh, I don’t care. You know, of course, how deeply it affects me and my whole life. I know your sympathy and good-fellowship. There’s not much more to say, is there?”

“Why, yes, Carleton; there is. As your friend, and also in the interests of justice, I am more than anxious to discover the villain who did the horrid deed, and though the inquest people are doing all they can, I want to add my efforts to theirs, in hope of helping them,—and you.”

“Don’t bother about me, Rob. I don’t care if they never discover the culprit. Miss Van Norman is gone; it can’t restore her to life if they do learn who killed her.”

Fessenden looked mystified.

“That’s strange talk, Schuyler,—but of course you’re fearfully upset, and I suppose just at first it isn’t surprising that you feel that way. But surely,—as man to man, now,—you want to find and punish the wretch that put an end to that beautiful young life.”

“Yes,—I suppose so;” Carleton spoke hesitatingly, and drew his hand across his brow in the same dazed way he did when in the witness box.

“You’re done up, old man, and I’m not going to bother you to-night. But I’m on the hunt, if you aren’t, and I’m going ahead on a few little trails, hoping they’ll lead to something of more importance. By the way, what were you doing in those few minutes last night between your entering the house and entering the library?”

Carleton stared at his guest.

“I don’t know what you mean,” he said.

“Yes, you do. You went in at eleven-fifteen, and you called for help at eleven-thirty.”

“No,—it didn’t take as long as that.” Carleton’s eyes had a far-away look, and Rob grasped his arm and shook him, as he said:

“Drop it, man! Drop that half-dazed way of speaking! Tell me, clearly, what did you do in that short interval?”

“I refuse to state,” said Carleton quietly, but with a direct glance now that made Fessenden cease his insistence.

“Very well,” he said; “it’s of no consequence. Now tell me what you were doing last evening before you went over to the house?”

At this Carleton showed a disposition to be both haughty and ironical.

“Am I being questioned,” he said, “and by you? Well, before I went to Miss Van Norman’s I was walking in the rose-garden with Miss Burt. You saw me from your window.”

“I did,” said Rob gravely. “Were you with Miss Burt until the time of your going over to the Van Norman house?”

“No,” said Carleton, with sarcastic intonation. “I said good-night to Miss Burt about three-quarters of an hour before I started to go over to Miss Van Norman’s. Do you want to know what I did during that interval?”

“Yes.”

“I was in my own room—my den. I did what many a man does on the eve of his wedding. I burned up a few notes,—perhaps a photograph or two,—and one withered rose-bud,—a ‘keepsake.’ Does this interest you?”

“Not especially, but, Schuyler, do drop that resentful air. I’m not quizzing you, and if you don’t want to talk about the subject at all, we won’t.”

“Very well—I don’t.”

“Very well, then.”

The two men rose, and as Carleton held out his hand Rob grasped it and shook it heartily, then they went to the drawing-room and rejoined the ladies.

The Van Norman affair was not mentioned again that evening.

All felt a certain oppression in the atmosphere, and all tried to dispel it, but it was not easy. Uninteresting topics of conversation were tossed from one to another, but each felt relieved when at last Mrs. Carleton rose to go upstairs and the evening was at an end.

Fessenden went to his room, his brain a whirlwind of conflicting thoughts.

He sat down by an open window and endeavored to classify them into some sort of order.

First, he was annoyed at Carleton’s inexplicable attitude. Granting he was in love with Miss Burt, he had no reason to act so unconcerned about the Van Norman tragedy. And yet Schuyler’s was a peculiar nature, and doubtless all this strange behavior of his was merely the effort to hide his real sorrow.

But again, if he were in love with Miss Burt, his sorrow for the loss of Madeleine was for the loss of her fortune and not herself. This Fessenden refused to believe, but the more he refused to believe it, the more it came back to him. Then there was his new notion, that came to him at dinner, about Miss Burt. Carleton said she was the ingenuous, timid girl she looked, but Rob couldn’t believe it. Executive ability showed in that determined little chin. Veiled cunning lurked in the shadows of those innocent eyes. And the girl had a mot

ive. Surely she wanted her rival out of her way. Then she had said good-night to Schuyler nearly an hour before he went over to Madeleine’s. Could she have—but, nonsense! Even if she had been so inclined, how could she have entered the house? Ah, that settled it! She couldn’t. And Fessenden was honestly glad of it. Honestly glad that he had proved to himself that Miss Burt—lovely, alluring little Dorothy Burt—was not the hardened criminal for whom he was looking!

Then it came back to Schuyler. No! Never Schuyler! But if not he, then who? And what was he doing in that incriminating interval, and why wouldn’t he tell?

And then, idly gazing from his window Rob saw again two figures walking in the rose-garden And they were the same two that he had seen there the evening before.

Schuyler Carleton and Dorothy Burt were strolling,—no, now they were standing, standing close to each other in earnest conversation.

Rob was no eavesdropper, and of course he couldn’t hear a word they said, but somehow he found it impossible to take his eyes from those two figures.

Steadily they talked,—so engrossed in their conversation that they scarcely moved; then Schuyler’s arm went slowly round the girl’s shoulders.

Gently she drew away, and he did not then again offer a caress.

Rob sat looking at them, saying frankly to himself that he was justified in doing so, since his motive effaced all consideration of puerile conventions. If that girl were really the designing young woman he took her to be,—more, if she could be the author, directly or indirectly, of that awful crime,—then Fessenden vowed he would save Schuyler from her fascinations at the risk of breaking their own lifelong friendship.

After further rapt and earnest conversation, Carleton took Miss Burt gently in his arms and kissed her lightly on the forehead. Then, drawing her arm through his own, they turned and walked slowly to the house.

A few moments later Rob heard the girl’s light footsteps as she came up to her room, but Carleton stayed down in the library until long after all the rest of the household were sleeping.

XV

FESSENDEN’S DETECTIVE WORK

NEXT MORNING ROB WENT over to the Van Norman house with a clearly developed plan of action. He declared to himself that he would allow no circumstance to shake his faith in his friend, that he would hold Carleton innocent of all wrongdoing in the affair, and that he would put all his ingenuity and cleverness to work to discover the criminal or any clue that might lead to such a discovery.

Although some questions he had wished to ask Cicely Dupuy were yet unanswered, Fessenden had discovered several important facts, and, after being admitted to the house, he looked about him for a quiet spot to sit down and tabulate them in black and white. The florist’s men were still in the drawing-room, so he went into the library. Here he found only Mrs. Markham and Miss Morton, who were apparently discussing a question on which they held opposite opinions.

“Come in, Mr. Fessenden,” said Mrs. Markham, as he was about to withdraw. “I should be glad of your advice. Ought I to give over the reins of government at once to Miss Morton?”

“Why not?” interrupted Miss Morton, herself. “The house is mine; why should I not be mistress here?”

Fessenden repressed a smile. It seemed to him absurd that these two middle-aged women should discuss an issue of this sort with such precipitancy.

“It seems to me a matter of good taste,” he replied. “The house, Miss Morton, is legally yours, but as its mistress, I think you’d show a more gracious manner if you would wait for a time before making any changes in the domestic arrangements.”

Apparently undesirous of pursuing the gracious course he recommended, Miss Morton rose abruptly and flounced out of the room.

“Now she’s annoyed again,” observed Mrs. Markham placidly. “The least little thing sets her off.”

“If not intrusive, Mrs. Markham, won’t you tell me how it comes about that Miss Morton inherits this beautiful house? Is she a relative of the Van Normans?”

“Not a bit of it. She was Richard Van Norman’s sweetheart, years and years and years ago. They had a falling-out, and neither of them ever married. Of course he didn’t leave her any of his fortune. But only a short time ago, long after her uncle’s death, Madeleine found out about it from some old letters. She determined then to hunt up this Miss Morton, and she did so, and they had quite a correspondence. She came here for the wedding, and Madeleine intended she should make a visit, and intended to give her a present of money when she went away. In the meantime Madeleine had made her will, though I didn’t know this until to-day, leaving the place and all her own money to Miss Morton. I’m not surprised at this, for Tom Willard has plenty, and as there was no other heir, I know Madeleine felt that part of her uncle’s fortune ought to be used to benefit the woman he had loved in his youth.”

“That explains Miss Morton, then,” said Fessenden. “But what a peculiar woman she is!”

“Yes, she is,” agreed Mrs. Markham, in her serene way. “But I’m used to queer people. Richard Van Norman used to give way to the most violent bursts of temper I ever saw. Maddy and Tom are just like him. They would both fly into furious rages, though I must say they didn’t do it often, and never unless for some deep reason.”

“And Mr. Carleton—has he a high temper?”

Mrs. Markham’s brow clouded. “I don’t understand that man,” she said slowly. “I don’t think he has a quick temper, but there’s something deep about him that I can’t make out. Oh, Mr. Fessenden, do you think he killed our Madeleine?”

“Do you?” said Fessenden suddenly, looking straight at her.

“I do,” she said, taken off her guard. “That is, I couldn’t believe it, only, what else can I think? Mr. Carleton is a good man, but I know Maddy never killed herself, and I know the way this house is locked up every night. No burglar or evil-doer could possibly get in.”

“But the murderer may have been concealed in the house for hours beforehand.”

“Nonsense! That would be impossible, with a house so full of people, and the wedding preparations going on, and everything. Besides, Mr. Hunt would have heard any intruder prowling around; and then again, how could he have gone out? Everything was bolted on the inside, except the front door, and had he gone out that way he must surely have been heard.”

“Well reasoned, Mrs. Markham! I think, with you, we may dismiss the possibility of a burglar. The time was too short for anything except a definitely premeditated act. And yet I cannot believe the act was that of Schuyler Carleton. I know that man very well, and a truer, braver soul never existed.”

“I know it,” declared Mrs. Markham, “but I think I’m justified in telling you this. Mr. Carleton didn’t love Madeleine, and he did love another girl. Madeleine worshipped him, and I think he came last night to ask her to release him, and she refused, and then—and then—”

Something about Mrs. Markham’s earnest face and sad, distressed voice affected Fessenden deeply, and he wondered if this theory she had so clearly, though hesitatingly, stated, could be the true one. Might he, after all, be mistaken in his estimate of Schuyler Carleton, and might Mrs. Markham’s suggestion have even a foundation of probability?

They were both silent for a few minutes, and then Mr. Fessenden said, “But you thought it was suicide at first.”

“Indeed I did; I looked at the paper through glasses that were dim with tears, and it looked to me like Madeleine’s writing. Of course Miss Morton also thought it was, as she was only slightly familiar with Maddy’s hand. But now that we know some one else wrote that message, of course we also know the dear girl did not bring about her own death.”

Mrs. Markham was called away on some household errands then, and Fessenden remained alone in the library, trying to think of some clue that would point to some one other than Carleton.

“I’m sure that man is not a murderer,” he declared to himself

. “Carleton is peculiar, but he has a loyal, honest heart. And yet, if not, who can have done the deed? I can’t seem to believe it really was either the Dupuy woman or the Burt girl, And I know it wasn’t Schuyler! There must have been some motive of which I know nothing. And perhaps I also know nothing of the murderer. It need not necessarily have been one of these people we have already questioned.” His thoughts strayed to the under-servants of the house, to common burglars, or to some powerful unknown villain. But always the thought returned that no one could have entered and left the house unobserved within that fatal hour.

And then, to his intense satisfaction, Kitty French came into the room.

“Good morning, Rose of Dawn,” he said, looking at her bright face. “Are you properly glad to see me?”

“Yes, kind sir,” she said, dropping a little curtsey, and smiling in a most friendly way.

“Well, then, sit down here, and let me talk to you, for my thoughts are running riot, and I’m sure you alone can help me straighten them out.”

“Of course I can. I’m wonderful at that sort of thing. But, first I’ll tell you about Miss Dupuy. She’s awfully ill—I mean prostrated, you know; and she has a high fever and sometimes she chatters rapidly, and then again she won’t open her lips even if any one speaks to her. We’ve had the doctor, and he says it’s just overstrained nerves and a naturally nervous disposition; but, Mr. Fessenden, I think it’s more than that; I think it’s a guilty conscience.”

“And yesterday, when I implied that Miss Dupuy might know more about it all than she admitted, you wouldn’t listen to a word of it!”

“Yes, I know it, but I’ve changed my mind.”

“Oh, you have; just for a change, I suppose.”

“No,” said Kitty, more seriously; “but because I’ve heard a lot of Cicely’s ranting,—for that’s what it is,—and while it’s been only disconnected sentences and sudden exclamations, yet it all points to a guilty knowledge of some sort, which she’s trying to conceal. I don’t say I suspect her, Mr. Fessenden, but I do suspect that she knows a lot more important information than she’s told.”

The Deep Lake Mystery

The Deep Lake Mystery The Man Who Fell Through the Earth

The Man Who Fell Through the Earth The Mystery of the Sycamore

The Mystery of the Sycamore The Mystery Girl

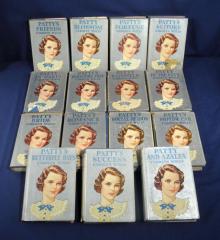

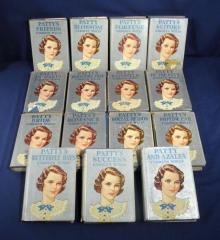

The Mystery Girl Patty Blossom

Patty Blossom Patty and Azalea

Patty and Azalea The Room with the Tassels

The Room with the Tassels The Vanishing of Betty Varian

The Vanishing of Betty Varian Murder in the Bookshop

Murder in the Bookshop The Staying Guest

The Staying Guest The Curved Blades

The Curved Blades Patty—Bride

Patty—Bride The Mark of Cain

The Mark of Cain Two Little Women on a Holiday

Two Little Women on a Holiday Marjorie's New Friend

Marjorie's New Friend Patty's Fortune

Patty's Fortune Patty's Social Season

Patty's Social Season Patty in Paris

Patty in Paris The Diamond Pin

The Diamond Pin The Come Back

The Come Back The Dorrance Domain

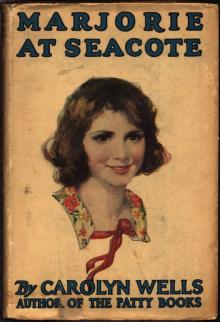

The Dorrance Domain Marjorie at Seacote

Marjorie at Seacote Patty's Butterfly Days

Patty's Butterfly Days Patty's Motor Car

Patty's Motor Car Patty's Success

Patty's Success Patty's Suitors

Patty's Suitors Patty's Summer Days

Patty's Summer Days Two Little Women

Two Little Women Patty Fairfield

Patty Fairfield Marjorie's Busy Days

Marjorie's Busy Days Betty's Happy Year

Betty's Happy Year In the Onyx Lobby

In the Onyx Lobby Marjorie's Maytime

Marjorie's Maytime The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK®

The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK® The Gold Bag

The Gold Bag The Clue

The Clue The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery

The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery