- Home

- Carolyn Wells

The Clue Page 10

The Clue Read online

Page 10

The district attorney, who had been comparing the papers, laid them down with an air of finality that proved his agreement with the statements made.

“And so,” went on Mr. Benson, “granting, as we must, that Miss Dupuy wrote the paper, we have nothing whatever to indicate that this case is a suicide. We are, therefore, seeking a murderer, and our most earnest efforts must be made to that end. I trust, Mr. Carleton, now that you can no longer think Miss Van Norman wrote the message, that you will aid us in our work by stating frankly how you were occupied during that quarter-hour which elapsed between your entering the house and your raising the alarm?”

But Carleton preserved his stony calm.

“There was no quarter-hour,” he said; “I may have stepped into the drawing-room a moment before going to the library, but I gave the alarm almost immediately on entering the house. Certainly immediately on my discovery of—of the scene in the library.”

Cicely looked defiantly at Mr. Hunt, who, in his turn, looked perplexed. The man had no wish to insinuate anything against Mr. Carleton, but as he had said, it was his business to know the time, and he knew that Mr. Carleton came into the house at quarter after eleven, and not at half-past.

The pause that followed was broken by Coroner Benson’s voice. “There is nothing more to be done at present. The inquest is adjourned until to-morrow afternoon. But we have discovered that there has been a crime committed. There is no doubt that Miss Van Norman was murdered, and that the crime took place between half-past ten and half-past eleven last night. It is our duty to spare no effort to discover the criminal. As an audience you are now dismissed.”

XII

DOROTHY BURT

THE PEOPLE ROSE SLOWLY from their chairs, and most of them looked as if they did not quite comprehend what it all meant. Among these was Carleton himself. He seemed oblivious to the fact that he was—at least tacitly—an accused man, and stood quietly, as if awaiting any further developments that might come.

“Look at Schuyler,” said Kitty French to Fessenden. The two had withdrawn to a quiet corner to discuss the affair. But Kitty was doing most of the talking, while Fessenden was quiet and seemed preoccupied. “Of course I suppose he must have killed Madeleine,” went on Kitty, “but it’s so hard to believe it, after all. I’ve tried to think of a reason for it, and this is the only one I can think of. They quarreled yesterday afternoon, and he went away in a huff. I believe he came back last night to make it up with her, and then they quarreled again and he stabbed her.”

Fessenden looked at her thoughtfully. “I think that Hunt man testified accurately,” he said. “And if so, Carleton was in the house just fifteen minutes before he gave the alarm. Now, fifteen minutes is an awfully short time to quarrel with anybody so desperately that it leads to a murder.”

“That’s true; but they both have very quick tempers. At least Madeleine had. She didn’t often do it, but when she did fly into a fury it was as quick as a flash. I’ve never seen Mr. Carleton angry, but I know he can be, for Maddy told me so.”

“Still, a quarter of an hour is too short a time for a fatal quarrel, I think. If Carleton killed her he came here for that purpose, and it was done premeditatedly.”

“Why do you say ‘if he killed her’? It’s been proved she didn’t kill herself; it’s been proved that no one could enter the house without a latch-key, and it’s been proved that the deed was done in that one hour between half-past ten and half-past eleven. So it had to be Mr. Carleton.”

“Miss French, you have a logical mind, and I think you’d make a clever little detective. But you have overlooked the possibility that she was killed by some one in the house.”

“Some of us?” Kitty’s look of amazement almost made Fessenden smile.

“Not you or Miss Gardner,” he said. “But a burglar might have been concealed in the house.”

“I never thought of that!” exclaimed Kitty, her eyes opening wide at the thought. “Why, he might have killed us all!”

“It isn’t a very plausible theory,” said Fessenden, unheeding the girl’s remark, “and yet I could think of nothing else. Every instinct of my mind denies Carleton’s guilt. Why, he isn’t that sort of a man!”

“Perhaps he isn’t as good as he looks,” said Kitty, wagging her head wisely. “I know a lot about him. You know he wasn’t a bit in love with Maddy.”

“You hinted that before. And was he really a mere fortune-hunter? I can’t believe that of Carleton. I’ve known the man for years.”

“He must have been, or else why did he marry her? He’s in love with another girl.”

“He is! Who?”

“I don’t know who. But Madeleine hinted it to me only a few days ago. It made her miserable. And that’s why everybody thought she wrote that paper that said, ‘I love S. but he does not love me.’”

“And you don’t know who this rival is?”

“No, but I know what she’s like. She’s the ‘clinging rosebud’ effect.”

“What do you mean?”

“Just that. You know Madeleine was a big, grand, splendid type,—majestic and haughty; and she thought Schuyler loved better some little, timid girl, who would sort of look up to him, and need his protection.”

Fessenden looked steadily at Miss French. “Are you imagining all this,” he said, “or is it true?”

“Both,” responded Kitty, with a charming little smile. “Maddy just hinted it to me, and I guessed the rest. You know, I have detective instinct too, as well as you.”

“You have, indeed;” and Rob gave an admiring glance to the pouting red lips, and roguish eyes. “But tell me more about it.”

“There isn’t much to tell,” said Kitty, looking thoughtful, “but there’s a lot to deduce.”

“Well, tell me what there is to tell, and then we’ll both deduce.”

It pleased Kitty greatly to imagine she was really helping Fessenden, and she went glibly on: “Why, you see, Maddy was unhappy,—we all know that,—and it was for some reason connected with Schuyler. Yet they were to be married, all the same. But sometimes Maddy has asked me, with such a wistful look, if I didn’t think men preferred little, kittenish girls to big, proud ones like herself.”

“And you, being a little, kittenish girl, said yes?”

“Don’t be rude,” said Kitty, flashing a smile at him. “I am kittenish in name only. And I am not little!”

“You are, compared to Miss Van Norman’s type.”

“Oh, yes; she was like a beautiful Amazon. Well, she either had reason to think, or she imagined, that Schuyler pretended to love her, and was really in love with some dear little clinging rosebud.”

“Clinging rosebud! What an absurd expression! And yet—by Jove!—it just fits her! And Miss Van Norman said to me—oh, I say, Miss French, don’t you know who the rosebud is.”

“No,” said Kitty, wondering at his sudden look of dismay.

“Well, I do! Oh, this is getting dreadful. Come outside with me and let’s look into this idea. I hope it’s only an idea!”

Throwing a soft fawn-colored cape round her, and drawing its pink-lined hood over her curly hair, Kitty went with Fessenden out on the lawn and down to the little arbor where they had sat before.

“Did you ever hear of Dorothy Burt?” he asked, almost in a whisper.

“No; who is she?”

“Well, she’s your ‘clinging rosebud,’ I’m sure of it! And I’ll tell you why.”

“First tell me who she is.”

“She’s Mrs. Carleton’s companion. Schuyler’s mother, you know. She lives in the Carleton household, and she is the sweetest, prettiest, shyest little thing you ever saw! ‘Clinging rosebud’ just fits her.”

“Indeed!” said Kitty, who had suddenly lost interest in the conversation. And indeed, few girls of Kitty’s disposition would have enjoyed this enthusiastic eu

logy of another.

“I don’t admire that sort, myself,” went on Rob, who was tactfully observant; “I like a little more spirit and vivacity.” Kitty beamed once more. “But she’s a wonder, of her own class. I was there at dinner last night, you know, and I saw her for the first time. And, though I thought nothing of it at the time, I can look back now and see that she adores Schuyler. Why, she scarcely took her eyes off him at dinner, and she ate next to nothing. Poor little girl, I believe she was awfully cut up at his approaching marriage.”

“And what was Schuyler’s attitude toward her?” Kitty was interested enough now.

Fessenden looked very grave and was silent for a time.

“It’s a beastly thing to say,” he observed at last, “but if Schuyler had been in love with that girl, and wanted to conceal the fact, he couldn’t have acted differently from the way he did act.”

“Was he kind to her?”

“Yes, kind, but with a restrained air, as if he felt it his duty to show indifference toward her.”

“Was she with you after dinner?”

Fessenden thought.

“I went to my room early; and Mrs. Carleton had then already excused herself. Yes,—I left Schuyler and Miss Burt in the drawing-room, and later I saw them from my window, strolling through the rose-garden.”

“On his wedding eve!” exclaimed Kitty, with a look akin to horror in her eyes.

“Yes; and I thought nothing of it, for I simply assumed that he was devoted to Miss Van Norman, and was merely pleasant to his mother’s companion. But—in view of something Miss Van Norman said to me yesterday—can it be it was only yesterday?—the matter becomes serious.”

“What did she say?”

“It seems like betraying a confidence, and yet it isn’t, for we must discover if it means anything. But she said to me, with real agitation, ‘Do you know Dorothy Burt?’ At that time, I hadn’t met Miss Burt, and had never heard of her, so I said: ‘No; who is she?’ ‘Nobody,’ said Miss Van Norman, ‘less than nobody! Never mention her to me again!’ Her voice, even more than her words, betokened grief and even anger, so of course the subject was dropped. But doesn’t that prove her anxious about the-girl, if not really jealous?”

“Of course it does,” said Kitty. “I know that’s the one that has been troubling Madeleine. Oh, how dreadful it all is!”

“And then, too,” Fessenden said, still reminiscently, “Miss Van Norman said she wanted to go away from Mapleton immediately after her wedding, and never return here again.”

“Did she say that! Then, of course, it was only so that Schuyler should never see the Burt girl again. Poor, dear Maddy; she was so proud, and so self-contained. But how she must have suffered! You see, she knew Schuyler admired her, and respected her and all that, and she must have thought that, once removed from the presence of the rosebud girl, he would forget her.”

“But I can’t understand old Schuyler marrying Miss Van Norman if he didn’t truly love her. You know, Miss French, that man and I have been stanch friends for years; and though I rarely see him, I know his honorable nature, and I can’t believe he would marry one woman while loving another.”

“He didn’t,” said Kitty in a meaning voice that expressed far more than the words signified.

Fessenden drew back in horror.

“Don’t!” he cried. “You can’t mean that Schuyler put Miss Van Norman out of the way to clear the path for Miss Burt!”

“I don’t mean anything,” said Kitty, rather contradictorily. “But, as I said, Maddy was not killed by any one inside the house—I’m sure of that—and no one from outside could get in, except Schuyler—and he had a motive. Don’t you always, in detective work, look for the motive?”

“Yes, but this is too horrible!”

“All murders are ‘too horrible.’ But I tell you it must have been Schuyler—it couldn’t have been Miss Burt!”

“Don’t be absurd! That little girl couldn’t kill a fly, I’m sure. I wish you could see her, Miss French. Then you’d understand how her very contrast to Miss Van Norman’s splendid beauty would fascinate Schuyler. And I know he was fascinated. I saw it in his repressed manner last evening, though I didn’t realize it then as I do now.”

“I have a theory,” said Kitty slowly. “You know Mr. Carleton went away yesterday afternoon rather angry at Maddy. She had carried her flirtation with Tom a little too far, and Mr. Carleton resented it. I don’t blame him,—the very day before the wedding,—but it was partly his fault, too. Well, suppose he went home, rather upset over the quarrel, and then seeing Miss Burt, and her probably mild, angelic ways (I’m sure she has them!)—suppose he wished he could be off with Maddy, and marry Miss Burt instead.”

“But he wouldn’t kill his fiancée, if he did think that!”

“Wait a minute. Then suppose, after the evening in the rose-garden with the gentle, clinging little girl, he concluded he never could be happy with Maddy, and suppose he came at eleven o’clock, or whatever time it was, to tell her so, and to ask her to set him free.”

“On the eve of the wedding day? With the house already in gala dress for the ceremony?”

“Yes, suppose the very nearness of the ceremony made it seem to him impossible to go through with it.”

“Well?”

“Well, and then suppose he did ask Madeleine to free him, and suppose she refused. And she would refuse! I know her nature well enough to know she never would give him up to the other girl if she could help it. And then suppose, when she refused to free him,—you know he has a fearfully quick temper, and that awful paper-cutter lay right there, handy,—suppose he stabbed her in a moment of desperate anger.”

“I can’t think it,” said Rob, after a pause; “I’ve tried, and I can’t. But, suppose all you say is true far as this; suppose he asked her to free him, because he loved another, and suppose she was so grieved and mortified at this, that in her own sudden fit of angry jealousy,—you know she had a quick temper, also,—suppose she picked up the dagger and turned it upon herself, as she had sometimes said she would do.”

Kitty listened attentively. “It might be so,” she said slowly; “you may be nearer the truth than I. But I do believe that one of us must be right. Of course, this leaves the written paper out of the question entirely.”

“That written paper hasn’t been thoroughly explained yet,” exclaimed the young man. “Now, look here, Miss French, I’m not going to wait to be officially employed on this case, though I am going to offer Carleton my legal services, but I mean to do a little investigating on my own account. The sooner inquiries are made, the more information is usually obtained. Can you arrange that I shall have an interview with Miss Dupuy?”

“I think I can,” said Kitty; “but if you let it appear that you’re inquisitive she won’t tell you a thing. Suppose we just talk to her casually, you and I. I won’t bother you.”

“Indeed you won’t. You’ll be of first-class help. When can we see her?”

While they had been talking, other things had been happening in the drawing-room. The people who had been gathered there had all disappeared, and, under the active superintendence of Miss Morton, the florist’s men who had put up the decorations were now taking them away. The whole room was in confusion, and Kitty and Mr. Fessenden were glad to escape to some more habitable place.

“Wait here,” said Kitty, as they passed through the hall, “and I’ll be back in a moment.”

Kitty flew upstairs, and soon returned, saying that Miss Dupuy would be glad to talk with them both in Madeleine’s sitting-room.

XIII

AN INTERVIEW WITH CICELY

THIS SITTING-ROOM WAS on the second floor, directly back of Madeleine’s bedroom, the bedroom being above the library. Miss Dupuy’s own room was back of this and communicated with it.

The sitting-room was a pleasant place, with larg

e light windows and easy chairs and couches. A large and well-filled desk seemed to prove the necessity of a social secretary, if Miss Van Norman cared to have any leisure hours.

Surrounded by letters and papers, Cicely sat at the desk as they entered, but immediately rose to meet them.

Kitty’s tact in requesting the interview had apparently been successful, for Miss Dupuy was gracious and affable.

But after some desultory conversation which amounted to nothing, Fessenden concluded a direct course would be better.

“Miss Dupuy,” he said, “I’m a detective, at least in an amateur way.”

Cicely gave a start and a look of fear came into her eyes.

“I have the interests of Schuyler Carleton at heart,” the young man continued, “and my efforts shall be primarily directed toward clearing him from any breath of suspicion that may seem to have fallen upon him.”

“O, thank you!” cried Cicely, clasping her hands and showing such genuine gratitude that Fessenden was startled by a new idea.

“I’m sure,” he said, “that you’ll give me any help in your power. As Miss Van Norman’s private secretary, of course you know most of the details of her daily life.”

“Yes; but I don’t see why I should tell everything to that Benson man!”

“You should tell him only such things as may have a bearing on this mystery that we are trying to clear up.”

“Then I know nothing to tell. I know nothing about the mystery.”

“No, Cicely,” said Kitty, in a soothing voice, “of course you know nothing definite; but if you could tell us some few things that may seem to you unimportant, we—that is, Mr. Fessenden—might find them of great help.”

“Well,” returned Cicely slowly, “you may ask questions, if you choose, Mr. Fessenden, and I will answer or not, as I prefer.”

“Thank you, Miss Dupuy.” You may feel sure I will ask only the ones I consider necessary to the work I have undertaken. And first of all, was Miss Van Norman in love with Carleton?”

The Deep Lake Mystery

The Deep Lake Mystery The Man Who Fell Through the Earth

The Man Who Fell Through the Earth The Mystery of the Sycamore

The Mystery of the Sycamore The Mystery Girl

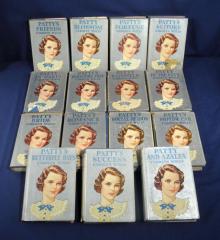

The Mystery Girl Patty Blossom

Patty Blossom Patty and Azalea

Patty and Azalea The Room with the Tassels

The Room with the Tassels The Vanishing of Betty Varian

The Vanishing of Betty Varian Murder in the Bookshop

Murder in the Bookshop The Staying Guest

The Staying Guest The Curved Blades

The Curved Blades Patty—Bride

Patty—Bride The Mark of Cain

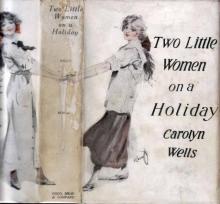

The Mark of Cain Two Little Women on a Holiday

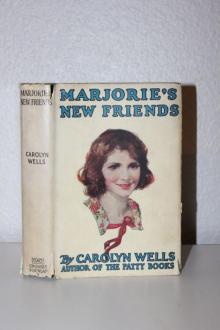

Two Little Women on a Holiday Marjorie's New Friend

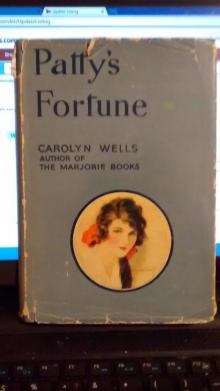

Marjorie's New Friend Patty's Fortune

Patty's Fortune Patty's Social Season

Patty's Social Season Patty in Paris

Patty in Paris The Diamond Pin

The Diamond Pin The Come Back

The Come Back The Dorrance Domain

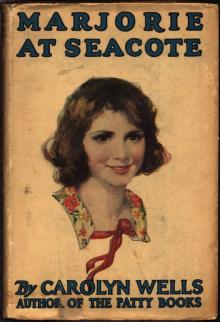

The Dorrance Domain Marjorie at Seacote

Marjorie at Seacote Patty's Butterfly Days

Patty's Butterfly Days Patty's Motor Car

Patty's Motor Car Patty's Success

Patty's Success Patty's Suitors

Patty's Suitors Patty's Summer Days

Patty's Summer Days Two Little Women

Two Little Women Patty Fairfield

Patty Fairfield Marjorie's Busy Days

Marjorie's Busy Days Betty's Happy Year

Betty's Happy Year In the Onyx Lobby

In the Onyx Lobby Marjorie's Maytime

Marjorie's Maytime The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK®

The Alan Ford Mystery MEGAPACK® The Gold Bag

The Gold Bag The Clue

The Clue The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery

The Gold Bag : A Fleming Stone Mystery